Spanish Gold

Matthew Walpole discovers a treasure of biblical proportions in the vaults of the Cathedral at Toledo.

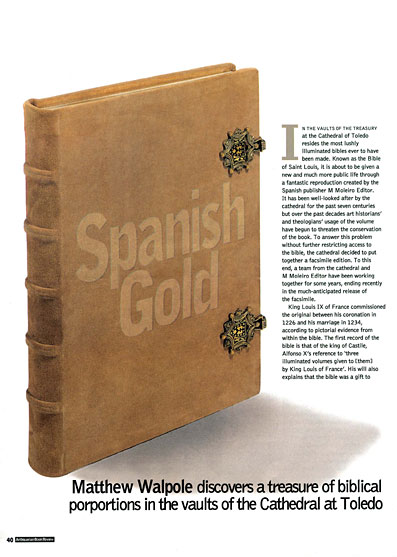

In the vaults of the treasury at the Cathedral of Toledo resides the most lushly illuminated bible ever to have been made. Known as the Bible of Saint Louis, it is about to be given a new and much more public life through a fantastic reproduction created by the Spanish publisher M. Moleiro Editor.

It has been well-looked after by the cathedral for the past seven centuries but over the past decades art historians' and theologians' usage of the volume have begun to threaten the conservation of the book. To answer this problem without further restricting access to the bible, the cathedral decided to put together a facsimile edition. To this end, a team from the cathedral and M. Moleiro Editor have been working together for some years, ending recently in the much-anticipated release of the facsimile.

King Louis IX of France commissioned the original between his coronation in 1226 and his marriage in 1234, according to pictorial evidence from within the bible. The first record of the bible is that of the king of Castile, Alfonso X's reference to "three illuminated volumes given to [them] by King Louis of France". His will also explains that the bible was a gift to King Alfonso from the French, so its presence in Spain is evidence of the kind of regal largesse that marked relations between Catholic countries.

The three volumes that constitute the Bible of Saint Louis are exceptional in every way. Most striking is the sheer quantity of illustration; through the 1,250 pages there are over 5,000 illustrations of biblical scenes. The sheer scale of the project was almost unheard of. The art historical value lies not merely in quantity, but among some surprising oddities that crop up in the book. For instance, most books on vellum use both side of the hide for illustrating and writing, but with books as heavily painted as the Bible of Saint Louis the vellum can only be used on one side. What is revolutionary about it is that rather than using the smoother flesh side of the vellum for illumination as was normal, they used the rougher hair side because it is able to carry more pigment.

It is not just the paintings that depart radically from what we might expect. The very name, bible, rather misleads because only about half of the text are canonical, the other half being biblical commentaries from a variety of authors. Unusually the commentaries are treated with the same opulent reverence that the bible stories themselves receive, which suggests how important they were thought to be. It is this peculiar balance of textual tradition and innovation that has made this a central text for the historical theologian. It gives a snapshot of what was happening across the Catholic world as well as the contemporary thought within Paris where the book was made.

That master bookmakers put the bible together is evidenced by the quality of the illustration. Which particular master bookmakers they may be, has not, as yet, been ascertained. It is an unusually well directed project, with a single authorial figure responsible for keeping the coherence of the book as work progressed on it. Who that was remains a mystery, but he did, in the most, achieve an extraordinary consistency of material within the three volumes. With this wealth of historical, theological and artistic material in the Saint Louis Bible, it inevitably commands a great deal of attention. Regular usage, of course, affects the book's condition and so the library is between a rock and hard place. As Francisco Álvarez Martínez, the Cardinal Archbishop, says: "We need to be sufficiently open to permit access to anyone interested in research on the Bible of Saint Louis, but we are equally aware of our duty to conserve what has been locked after so many centuries with such zeal." It is a bind that many libraries have faced and high quality facsimiles seem more and more often to be the corrective to the problem. The M. Moleiro Editor edition of the Saint Louis Bible should solve the problem of access for the cathedral. The original Bible of Saint Louis will now remain resplendent in the vaults of the Cathedral of Toledo, while the facsimile means that it can be consulted across the globe.

It exists in an edition of 987 numbered and authenticated editions on handmade paper with the same feel, thickness and smell as the original. It exists, of course, in the original three-volume format each measuring roughly 30cm by 40cm.

This is a treasure that doubtless all the major public libraries will lay their hands on but that only a handful of collectors will be able to acquire.

Matthew Walpole