The Glory of Bizantium

The Glory of Byzantium

Art and Culture of the Middle Byzantine Era

AD. 843-1261

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

Distributed by Harry N. Abrams, Inc. New York

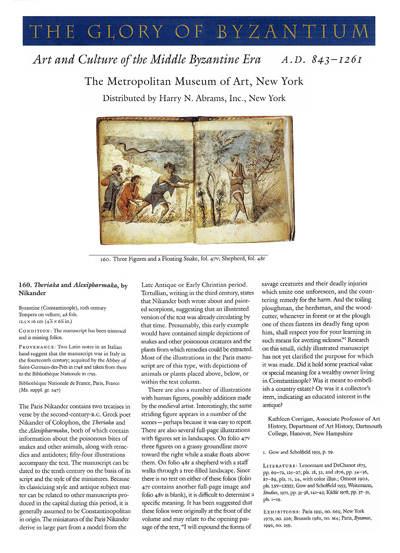

160. Theriaka and Alexipharmaka, by Nikander

Byzantine (Constantinople), 10th century

Tempera on vellum; 48 fols.

12,5 x 16 cm (4 7/8 x 6 1/4 in.)

Condition: The manuscript has been trimmed and is missing folios.

Provenance: Two Latin notes in an Italian hand suggest that the manuscript was in Italy in the Fourteenth century; acquired by the Abbey of Saint-Germain-des-Prés in 1748 and taken from there to the Bibliothèque Nationale in 1795.

Bibliothèque Nationale de France, Paris, France (Ms. suppl. gr. 247)

The Paris Nikander contains two treatises in verse by the second-century-B.C. Greek poet Nikander of Colophon, the Theriaka and the Alexipharmaka, both of which contain information about the poisonous bites of snakes and other animals, along with remedies and antidotes; fifty-four illustrations accompany the text. The manuscript can be dated to the tenth century on the basis of its script and the style of the miniatures. Because its classicizing style and antique subject matter can be related to other manuscripts poduced in the capital during this period, it is generally assumed to be Constantinopolitan in origin. The miniatures of the Paris Nikander derive in large part from a model from the Late Antique or Early Christian period.

Tertullian, writing in the third century, states that Nikander both wrote about and painted scorpions, suggesting that an illustrated version of the text was already circulating by that time. Presumably, this early example would have contained simple depictions of snakes and other poisonous creatures and the plants from which remedies could be extracted. Most of the illustrations in the Paris manuscript are of this type, with depictions of animals or plants placed above, below, or within the text column.

There are also a number of illustrations with human figures, possibly additions made by the medieval artist. Interestingly, the same striding figure appears in a number of the scenes – perhaps because it was easy to repeat. There are also several full-page illustrations with figures set in landscapes. On folio 47v three figures on a grassy groundline move toward the right while a snake floats above them. On folio 48r a shepherd with a staff walks through a tree-filled landscape. Since there is no text on either of these folios (folio 47r contains another full-page image and folio 48v is blank), it is difficult to determine a specific meaning. It has been suggested that these folios were originally at the front of the volume and may relate to the opening passage of the text, “I will expound the forms of savage creatures and their deadly injuries which smite one unforeseen, and the countering remedy for the harm. And the toiling ploughman, the herdsman, and the woodcutter, whenever in forest or at the plough one of them fastens its deadly fang upon him, shall respect you for your learning in such means for averting sickness.” Research on this small, richly illustrated manuscript has not yet clarified the purpose for which it was made. Did it hold some practical value or special meaning for a wealthy owner living in Constantinople? Was it meant to embellish a country estate? Or was it a collector’s item, indicating an educated interest in the antique?

Kathleen Corrigan, Associate Professor of Art History, Department of Art History, Dartmouth College, Hanover, New Hampshire

Exhibitions: Paris 1931, no. 663; New York 1979, no. 226; Brussels 1982, no. M4; Paris, Byzance, 1992, no. 259.