Illustrating the Nativity scene at the end of the 15th century

By Roger S. Wieck and Séverine Lepape

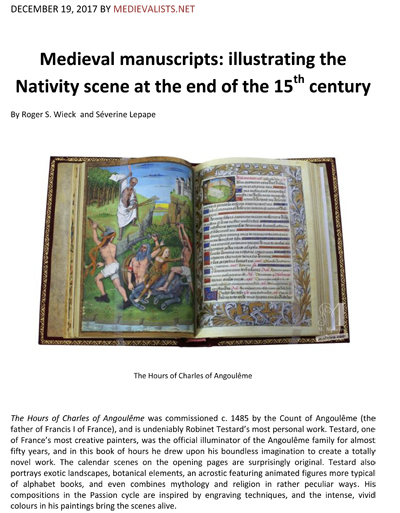

The Hours of Charles of Angoulême was commissioned c. 1485 by the Count of Angoulême (the father of Francis I of France), and is undeniably Robinet Testard’s most personal work. Testard, one of France’s most creative painters, was the official illuminator of the Angoulême family for almost fifty years, and in this book of hours he drew upon his boundless imagination to create a totally novel work. The calendar scenes on the opening pages are surprisingly original. Testard also portrays exotic landscapes, botanical elements, an acrostic featuring animated figures more typical of alphabet books, and even combines mythology and religion in rather peculiar ways. His compositions in the Passion cycle are inspired by engraving techniques, and the intense, vivid colours in his paintings bring the scenes alive.

Around the same time (c. 1500), in England, the illuminator Jean Poyer finished his masterpiece, The Hours of Henry VIII. This red-velvet bound manuscript is good proof of his reputation: he was famous for being a master colourist and a genius at composition and perspective. The beauty of the Franciscan Calendar, among other sections as the Office of the Dead and the Hours of the Virgin, makes this manuscript a peerless treasure.

THE HOURS OF CHARLES OF ANGOULÊME: Nativity, f. 18v

The Nativity appears between matins of the Holy Ghost (f. 18) and prime of the Hours of the Virgin (f. 19). This scene was often used to illustrate prime in the Hours of the Virgin in medieval books of hours.

At first sight this image looks like a painting, but in fact it is an engraving by Israhel van Meckenem copied from a print by Martin Schongauer, a great Rhinish artist and engraver in the last quarter of the 15th century. Schongauer is reckoned to have produced this print in c. 1480, so Israhel van Meckenem probably copied it shortly afterwards.

Testard altered Our Lady’s face in the print to make her look downwards tenderly and respectfully at the son of God. Because the print was too short (Testard probably had a trimmed print with no margins), the illuminator had to fill the upper area and did so by painting the rest of the sloping thatched roof. He also added many details to the background and used a simple golden line for Our Lady’s halo instead of the solid disk that hid the landscape in the original print. He moved the two wooden beams wedged against the brick wall to prop the roof up, and added a tree. He extended the illumination downwards by simply painting the visible parchment green. Testard was careful to hide Israhel van Meckenem’s initials under a few extra stalks of hay.

This is the only print in the main part of the Hours of Charles of Angoulême, i.e. the actual Hours. All the other images (Annunciation, Pentecost, Adoration of the Magi, etc) are illuminations done either by Jean Bourdichon or Robinet Testard. It should, however, have been quite easy for Robinet Testard to create an illumination of the Nativity, an extremely common subject, so his use of a print is very surprising. Testard might either have set his heart on using Meckenem’s northern composition or used this print to save time when decorating the book. In the absence of further details, this question remains unanswered.

THE HOURS OF HENRY VIII: Nativity, f. 51v

Prior to the fourteenth century, the iconography of the Nativity had the Virgin reclining, resting after having given birth, with the Christ Child, in swaddling clothes, lying in a manger. The fourteenth-century visions of St. Bridget of Sweden (c. 1303-1373), however, changed the way the Nativity was depicted in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries. Poyer’s miniature reflects this trend of influence. The Virgin kneels on the bare ground, her hands raised in a gesture of worship. Joseph, too, kneels and folds his hands in prayer. The Christ Child lies naked in the manger, not clothed, and he shines like a bright light, emitting golden rays that illuminate the figures of Mary and Joseph and their clothing. (In other depictions of the Nativity influenced by Bridget, the naked Savior will lie directly on the ground.) The ox and ass (not mentioned in the Gospels, but included by Bridget) sometimes offer their warming breath to the Child, but Poyer in his miniature prefers their exegetical connection with the Nativity. The animals represent the break between the Old and New Dispensation, that is, the Old and New Law. The ox, symbolizing the New Law of Christ knowingly looks on; the ass, representing the Old Law of Moses, wandering about, his view blocked, is thus uncomprehending. At the bottom left is the ass’s saddle, upon which Mary rode on her trip to Bethlehem.

In the background, three shepherds – the annunciation to whom is the subject of the following miniature – hesitantly approach the scene. The inclusion of shepherds in the Nativity is a motif championed by Jean Fouquet. As Nicole Reynaud has observed, Fouquet includes shepherds in the Nativities in both the Hours of Étienne Chevalier and the Raguier-Robertet Hours. Following his teacher, Jean Colombe includes them in the Nativity he painted in the Hours of Louis de Laval, a manuscript that had influence within Poyer’s workshop. Thus Poyer could have been influenced by both Fouquet and Colombe in composing his Nativity in the Hours of Henry VIII.

This was an excerpt from The Hours of Henry VIII commentary volume by Séverine Lepape (Bibliothèque nationale de France) and The Hours of Henry VIII commentary volume, by Roger S. Wieck (Curator and Department Head of Medieval and Renaissance Manuscripts at The Morgan Library & Museum). Our thanks to Moleiro Editor for this text and images. You can learn more about this at: www.moleiro.es