The Hours of Charles of Angoulême

BY SÉVERINE LEPAPE AND MAXENCE HERMANT

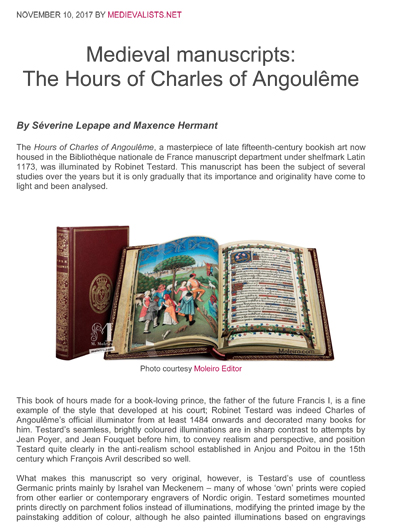

The Hours of Charles of Angoulême, a masterpiece of late fifteenth-century bookish art now housed in the Bibliothèque nationale de France manuscript department under shelfmark Latin 1173, was illuminated by Robinet Testard. This manuscript has been the subject of several studies over the years but it is only gradually that its importance and originality have come to light and been analysed.

This book of hours made for a book-loving prince, the father of the future Francis I, is a fine example of the style that developed at his court; Robinet Testard was indeed Charles of Angoulême’s official illuminator from at least 1484 onwards and decorated many books for him. Testard’s seamless, brightly coloured illuminations are in sharp contrast to attempts by Jean Poyer, and Jean Fouquet before him, to convey realism and perspective, and position Testard quite clearly in the anti-realism school established in Anjou and Poitou in the 15th century which François Avril described so well.

What makes this manuscript so very original, however, is Testard’s use of countless Germanic prints mainly by Israhel van Meckenem – many of whose ‘own’ prints were copied from other earlier or contemporary engravers of Nordic origin. Testard sometimes mounted prints directly on parchment folios instead of illuminations, modifying the printed image by the painstaking addition of colour, although he also painted illuminations based on engravings which he probably owned.

This innovative and hitherto unknown use of prints to decorate a book of hours is an indication of the painter’s keen interest in the novel iconographic and formal traits of prints, a very new medium that appeared for the first time in Europe in the early 15th century and in France from 1460-1470 onwards. It probably also reflects the manuscript patron’s fondness for prints and even his involvement in the decision to use them in his book of hours.

Charles of Angoulême is indeed known to have had a large library of printed books and was in contact with Antoine Vérard, a great bookseller who commissioned and sold printed books, many of which were magnificent, at a time when few princely patrons ventured into the realm of mass-produced books. As a result, the Hours of Charles of Angoulême has plenty of surprises in store for lovers of illuminated manuscripts.

Two illuminators with completely different styles worked on the Hours of Charles of Angoulême: Robinet Testard, who may be described as the main illuminator, and Jean Bourdichon, who only contributed a few folios. Robinet Testard, originally from Poitiers judging by the first works attributed to him, was the official illuminator of the Angoulême family for almost fifty years.

The Hours of Charles of Angoulême, a masterpiece of late fifteenth-century bookish art now housed in the Bibliothèque nationale de France manuscript department under shelfmark Latin 1173, was illuminated by Robinet Testard. This manuscript has been the subject of several studies over the years but it is only gradually that its importance and originality have come to light and been analysed.

This book of hours made for a book-loving prince, the father of the future Francis I, is a fine example of the style that developed at his court; Robinet Testard was indeed Charles of Angoulême’s official illuminator from at least 1484 onwards and decorated many books for him. Testard’s seamless, brightly coloured illuminations are in sharp contrast to attempts by Jean Poyer, and Jean Fouquet before him, to convey realism and perspective, and position Testard quite clearly in the anti-realism school established in Anjou and Poitou in the 15th century which François Avril described so well.

What makes this manuscript so very original, however, is Testard’s use of countless Germanic prints mainly by Israhel van Meckenem – many of whose ‘own’ prints were copied from other earlier or contemporary engravers of Nordic origin. Testard sometimes mounted prints directly on parchment folios instead of illuminations, modifying the printed image by the painstaking addition of colour, although he also painted illuminations based on engravings which he probably owned.

This innovative and hitherto unknown use of prints to decorate a book of hours is an indication of the painter’s keen interest in the novel iconographic and formal traits of prints, a very new medium that appeared for the first time in Europe in the early 15th century and in France from 1460-1470 onwards. It probably also reflects the manuscript patron’s fondness for prints and even his involvement in the decision to use them in his book of hours.

Charles of Angoulême is indeed known to have had a large library of printed books and was in contact with Antoine Vérard, a great bookseller who commissioned and sold printed books, many of which were magnificent, at a time when few princely patrons ventured into the realm of mass-produced books. As a result, the Hours of Charles of Angoulême has plenty of surprises in store for lovers of illuminated manuscripts.

Two illuminators with completely different styles worked on the Hours of Charles of Angoulême: Robinet Testard, who may be described as the main illuminator, and Jean Bourdichon, who only contributed a few folios. Robinet Testard, originally from Poitiers judging by the first works attributed to him, was the official illuminator of the Angoulême family for almost fifty years.

The second image in the diptych about rearing domestic pigs, the month of November under the sign of Sagittarius, depicts the pig being slaughtered. Once salted or smoked, pork could last a long time, as a result of which pork was the meat eaten most, even more than lamb or beef. The pig sticking is depicted in quite a timeless, neutral indoor setting reminiscent of the July scene, with a masonry wall delimiting the scene to the rear. The floor features alternating pale blue and salmon pink tiles in an attempt to give the scene a sense of perspective. The pig has not been stunned beforehand, so the peasant has laid it on its right side and pinned it to the floor by holding its left rear leg down with his own leg, and its left front leg with his hand. He plunges his knife into the pig’s throat, severing its jugular vein and carotid artery. The blood drains out and the animal quickly dies. The blood, used to make black pudding, is collected by the female peasant in a long-handled pan which she holds firmly in one hand whilst stirring the blood with a spatula in her other hand to stop it coagulating.

The second image in the diptych about rearing domestic pigs, the month of November under the sign of Sagittarius, depicts the pig being slaughtered. Once salted or smoked, pork could last a long time, as a result of which pork was the meat eaten most, even more than lamb or beef. The pig sticking is depicted in quite a timeless, neutral indoor setting reminiscent of the July scene, with a masonry wall delimiting the scene to the rear. The floor features alternating pale blue and salmon pink tiles in an attempt to give the scene a sense of perspective. The pig has not been stunned beforehand, so the peasant has laid it on its right side and pinned it to the floor by holding its left rear leg down with his own leg, and its left front leg with his hand. He plunges his knife into the pig’s throat, severing its jugular vein and carotid artery. The blood drains out and the animal quickly dies. The blood, used to make black pudding, is collected by the female peasant in a long-handled pan which she holds firmly in one hand whilst stirring the blood with a spatula in her other hand to stop it coagulating.

The only illumination in the manuscript that can be attributed entirely to Jean Bourdichon, i.e. the Adoration of the Magi, appears at the beginning of sext of the Hours of the Virgin, the Cross and the Holy Ghost. It depicts the moment in the Gospel according to St Matthew (2: 1-12) when the Magi (originally described as wise men but subsequently referred to traditionally as kings, called Melchior, Gaspar and Balthazar) arrive at Christ’s birthplace after following a star. They consider him to be the king of the Jews and give him gold, frankincense and myrrh.

Bourdichon’s illumination depicts the three kings in lavish garments of gold brocade with beards to symbolise their wisdom, carrying their gifts in golden or silver-gilt goblets. From the central Middle Ages onwards, these figures were often regarded as representing the three ages of life: youth, middle age and old age. The king with the white beard in the Hours of Charles of Angoulême, Melchior, symbolises old age, but it is difficult to decide which of the two kings behind him is which because they both have beards (Gaspar, the king of youth, should have no beard). Bourdichon’s image does not feature an iconographic element popularised by Jacobus de Voragine in the late 13th century, i.e. a black Balthazar. The focal point of the illuminator’s scene is the present that Melchior is giving to the Child Jesus on Our Lady’s lap. She is depicted in the style typical of Bourdichon with part of her veil hanging down from her right temple and draped around below her left shoulder. Several beams and a hole in the wall suggest a stable but the ox and ass are nowhere to be seen.

This scene by Bourdichon is obviously indebted to the Master of the Munich Boccaccio who taught the former his craft in Jean Fouquet’s atelier. The two kings and the figure immediately behind them are inspired mainly, apart from a few modifications and alterations, by a group of three prophets in the Hours of Bourbon-Vendôme (BnF, Arsenal, ms. 417, f. 23v), which was, moreover, a manuscript that the young Bourdichon worked on. The compact crowd in the background is also a continuation of the work of Fouquet and the Master of the Munich Boccaccio.

The entire scene is surrounded by a false frame upon an imitation green marble ground, making the illumination look like an actual devotional painting. This frame, which has an inscription at the bottom, cannot date from the mid 1480s, the date accepted for the Hours of Charles of Angoulême: frames of this type are not found in other works by Bourdichon until at least a decade later. A closer analysis has, however, revealed that this folio is mounted on a stub, so the manuscript could have been altered subsequently, in the 1490s, for some unknown reason.

This was an excerpt from the Hours of Charles of Angoulême commentary volume by Séverine Lepape (curator at the Musée du Louvre) and Maxence Hermant (curator at the Bibliothèque Nationale de France). Our thanks to Moleiro Editor for this text and images.

Bourdichon’s illumination depicts the three kings in lavish garments of gold brocade with beards to symbolise their wisdom, carrying their gifts in golden or silver-gilt goblets. From the central Middle Ages onwards, these figures were often regarded as representing the three ages of life: youth, middle age and old age. The king with the white beard in the Hours of Charles of Angoulême, Melchior, symbolises old age, but it is difficult to decide which of the two kings behind him is which because they both have beards (Gaspar, the king of youth, should have no beard). Bourdichon’s image does not feature an iconographic element popularised by Jacobus de Voragine in the late 13th century, i.e. a black Balthazar. The focal point of the illuminator’s scene is the present that Melchior is giving to the Child Jesus on Our Lady’s lap. She is depicted in the style typical of Bourdichon with part of her veil hanging down from her right temple and draped around below her left shoulder. Several beams and a hole in the wall suggest a stable but the ox and ass are nowhere to be seen.

This scene by Bourdichon is obviously indebted to the Master of the Munich Boccaccio who taught the former his craft in Jean Fouquet’s atelier. The two kings and the figure immediately behind them are inspired mainly, apart from a few modifications and alterations, by a group of three prophets in the Hours of Bourbon-Vendôme (BnF, Arsenal, ms. 417, f. 23v), which was, moreover, a manuscript that the young Bourdichon worked on. The compact crowd in the background is also a continuation of the work of Fouquet and the Master of the Munich Boccaccio.

The entire scene is surrounded by a false frame upon an imitation green marble ground, making the illumination look like an actual devotional painting. This frame, which has an inscription at the bottom, cannot date from the mid 1480s, the date accepted for the Hours of Charles of Angoulême: frames of this type are not found in other works by Bourdichon until at least a decade later. A closer analysis has, however, revealed that this folio is mounted on a stub, so the manuscript could have been altered subsequently, in the 1490s, for some unknown reason.

This was an excerpt from the Hours of Charles of Angoulême commentary volume by Séverine Lepape (curator at the Musée du Louvre) and Maxence Hermant (curator at the Bibliothèque Nationale de France). Our thanks to Moleiro Editor for this text and images.