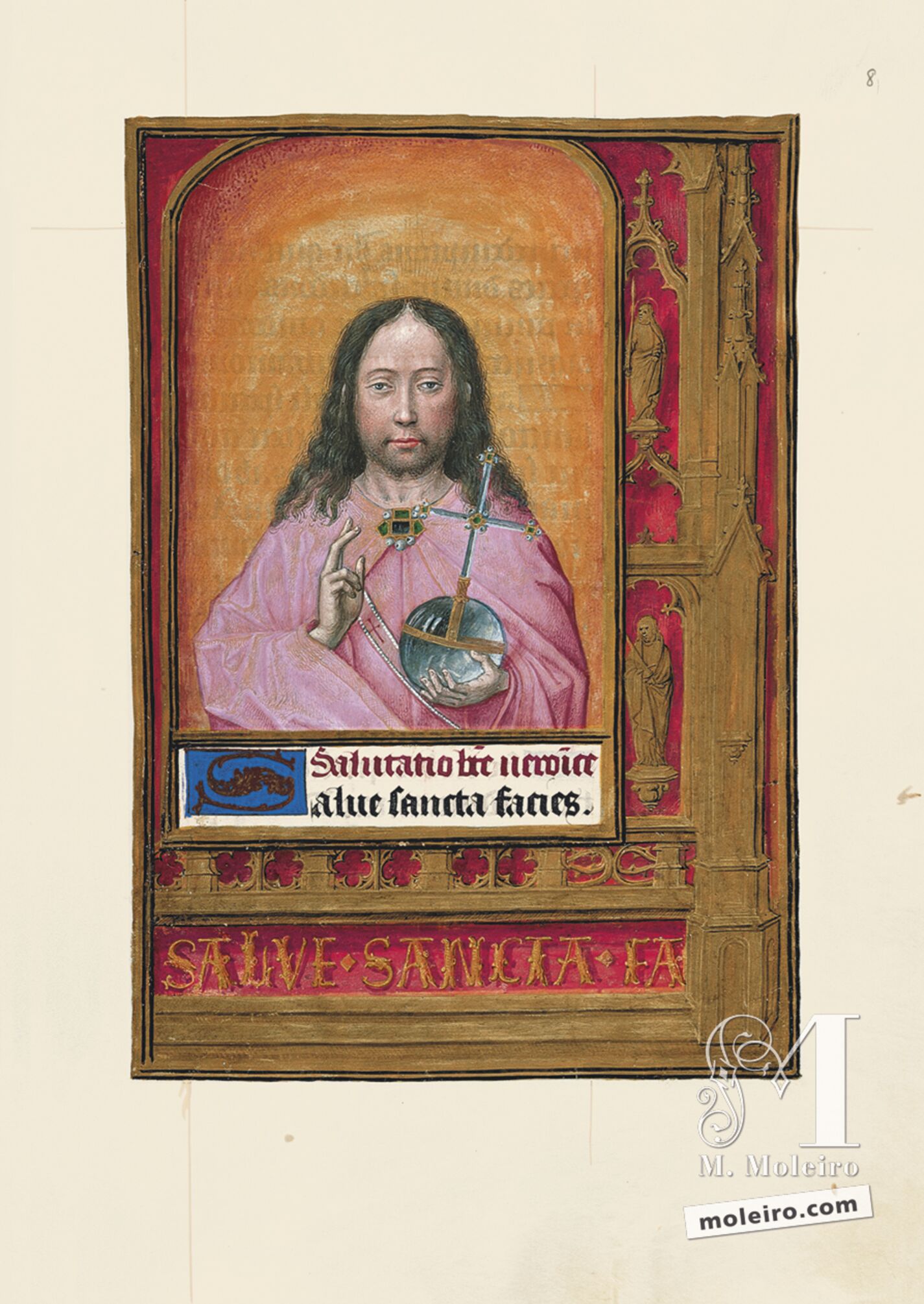

When the prayer to the holy face – an accessory element in books of hours that was particularly common in Flemish hours of the late 15th and early 16th centuries– is illustrated, it usually shows Christ’s face in the form of Veronica’s veil, in an allusion to the text. In the West, the devotion to the holy face was based particularly on Veronica’s sacred sudarium, a relic housed, since the 12th century at least, in St Peter’s basilica in Rome. The image chosen for the Hours of Joanna of Castile, however, is that of the Salvator mundi, in the form of a triumphant Christ, like a universal sovereign, with a young face, long hair and a long beard, in line, on the one hand, with the iconography used for Greek philosophers and pedagogues, and, on the other, the description of Jesus that Publius Lentulus, Pontius Pilate’s predecessor, gave in an epistle sent to the Roman senate. According to him, he had dark, shoulder-length hair the colour of wine with a parting in the middle and a thick, forked beard the same colour as his hair. The letter from Publius Lentulus emphasises his handsome face. The painting in the Hours of Joanna of Castile shows the Lord facing straight forwards, a detail that indicates his omniscience and importance. With his right hand, he makes a Latin blessing, i.e. with his thumb, index finger and middle fingers outstretched in reference to the Holy Trinity, whilst his left hand grasps a large glass sphere divided into three parts by two gold bands in what is clearly a reference to the three known continents, in keeping with the Isidorian representations of the world based on the OT formula. Upon this sphere, in the part where Jerusalem would be, is a large, Greek cross with its centre and tips made of gold and embellished with emeralds and pearls. Depicted in the background is the luminous irradiation of the Lord. The portrait is surrounded by a narrow, golden, bevelled frame, with the rubric and the beginning of the prayer “Salutatio b[ea]te uero[n]ice/Salue sancta facies” written upon its lower part. The trompe-l’oeil technique makes the painting of the Saviour’s face stand out against an architectonic type of border reminiscent of a late Gothic reredos, featuring, alongside the pinnacles and beneath polylobulated arches, the representations of two martyred saints upon pedestals. The one at the top bears a spear and the one below, a sword. Beneath late Gothic tracery, written in letters formed by woody acanthus stems, is the beginning of the prayer to the holy face “salve · sancta · fac”.

The Salvator mundi image originated in the East. Firstly, it is influenced by the ancient Greek portrait formula in which the bust is surrounded by a rectangular frame. The image of Christ stemmed from the official effigies of emperors – sacrae imagines – or consuls, a process that began towards the 4th century in the form of certain iconographic models alluding, in general terms, to the concepts of sovereignty, victory, power and justice. The christianised image was to evolve into the iconography of the Pantocrator, blessing but holding a book, inspired by the Byzantine Palaios tôn hêmerôn, showing the glory of Christ and his divine nature as opposed to his human nature undergoing suffering and death, i.e. conceived of as an eternal Christ and not as Jesus Christ incarnated. In Ottonian miniatures on the other hand, the figure of Christ made use of images of imperial power such as the orb, usually held in the left hand, symbolising, in this context, the universal domain of the Saviour. The bust image of the Salvator Mundi, however, shows Christ as the king of glory, the title with which he often occupies the upper part of Trecento reredos. After all these antecedents, it was in the Netherlands where the Salvator mundi assumed its definitive form: Christ depicted frontally as the king of glory in regal garb with his right hand raised in blessing and holding the globe in his left. During the 15th century the motif was replaced by images concentrating on the Saviour’s sufferings. Nevertheless, after the middle of that century, the popularity of the Salvator mundi theme increased considerably in the Netherlands, above all in the realm of devotional art for personal use and for book illustration, and began to spread into Dutch miniatures. Most of the books of hours produced in the last two decades of that century in the Ghent and Bruges area featured a Salvator mundi portrait, an image so popular that it persisted in the 16th century as can be seen in Simon Bening’s Flowers book of hours (Munich, Bayerische Staatsbibliothek, Clm 23637, f. 7v). Its forerunners in Flanders must include a panel attributed to Jan van Eyck (Bruges, Groeningemuseum), dated around January 1440. However, in the Netherlands, although painters were fond of this image, it was not subsequently developed in narrative scenes due to the lack of an appropriate context for the figure to appear in: no evangelical narration could feature a regal Saviour. In Italy, where iconography varied more than in the north, the opposite occurred for they did not attempt to represent a tale and insert the image into a static context to highlight the original concept of the Salvator Mundi: the power and glory of God. This image was, in turn, a useful aid to contemplation without the text. Like many medieval Christians, the owners of books of hours believed that contemplating images of this type was in itself a sort of prayer. As a result, this type of devotional manuscript created a physical and psychic space for solitude and contemplation in which the image of the Salvator Mundi even became a father, friend or confidant in whom to confide one’s sorrow or joy.