Epiphany in The Great Hours of Anne of Brittany

By Carlos Miranda García-Tejedor

The Great Hours of Anne of Brittany is undoubtedly a masterpiece of French painting, as is fitting for a manuscript intended for someone who was twice queen of France: with Charles VIII and then Louis XII.

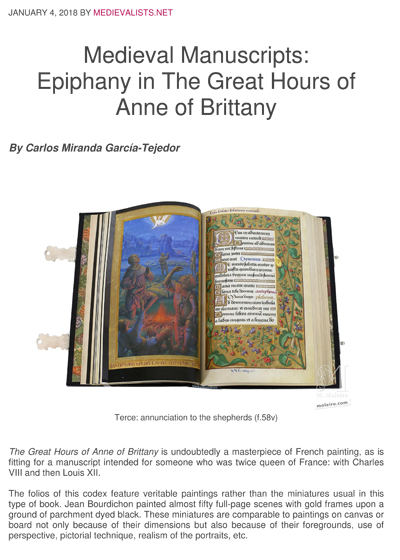

The folios of this codex feature veritable paintings rather than the miniatures usual in this type of book. Jean Bourdichon painted almost fifty full-page scenes with gold frames upon a ground of parchment dyed black. These miniatures are comparable to paintings on canvas or board not only because of their dimensions but also because of their foregrounds, use of perspective, pictorial technique, realism of the portraits, etc.

Master Bourdichon was court painter to Louis XI, Charles VIII, Louis XII and Francis I, and his paintings clearly contributed to the Gothic to Renaissance evolution.

Following the death of the duchess of Brittany in 1514, her Great Hours enthralled Louis XIV who transferred them to the “curiosities cabinet” at the palace of Versailles. This beautiful codex subsequently enraptured Napoleon III, who exhibited it at the Musée des Souverains in the Louvre from 1852 to 1872. It is now one of the most highly-prized treasures of the Bibliothèque nationale de France. Not in vain do art historians deem The Great Hours of Anne of Brittany to be one of the most outstanding books of hours in existence.

Epiphany Scene

Shining above the holes in the stable adjoining the classical building in ruins is the star which must be understood to be both the star leading the three Wise Men and the star of Jacob that identified Christ as the prophesied Messiah. Carolingian artists borrowed compositions from fourth- and fifth-century sarcophagi, highlighting the majesty of Our Lady and Jesus by situating the scene in an architectonic setting evoking the house mentioned in Matthew 2: 11. Leaning upon his staff in the background is St Joseph watching Our Lady sitting in the foreground presenting the naked puer senex Child, with his legs crossed to symbolise power and his hand raised in blessing, seated in her lap. In front of him, opening a casket of gold escudos, kneels Melchior, an old, bald man with his crown in the crook of his left arm, as in the Hours of Louis XII. His naturalist appearance endows him with powerful individual traits and is a prop enabling spectators to imagine and, in line with modern devotion, etch the Epiphany scene upon their memory more realistically.Behind him, pointing at Jesus with the gesture of warning advocated by Leon Battista Alberti, is Gaspar shown as a middle-aged man holding a large, gold, secular, lidded goblet containing incense. Behind them is Balthazar, the black king with earrings as an exotic attribute, holding his gift in his hands: a casket containing myrrh. Melchior’s gold represents royalty; Gaspar’s incense, divinity; and Balthazar’s myrrh, humanity, and consequently the Lord’s Passion. Since the 13th century the vessels in which the gold, frankincense and myrrh were presented were in the shape of liturgical vessels or ornate goblets belonging to a princely plate. It must be said that the main colors in this composition are white, green, red and ultramarine, possibly to suggest royalty. In the background is the retinue consisting of a servant with a large bundle in his arms, several soldiers with shields and spears on horseback and another, in a demonstration of luxury and exoticism, riding a camel. To the left, through the opening in the stable, a crowd of soldiers and civilian dignitaries can be seen, one of whom, whose pointed headwear indicates he is Jewish, points at the scene in the foreground whilst talking to another man in a turban.

Also shown in this image is the Wise Men’s garb: the Phrygian cap subsequently replaced by crowns from the 10th century onwards. Images from the early fourth century onwards depict what was to become a regular feature: the Mother of God in semi profile seated and holding the Child on her lap; the Wise Men opposite moving towards her bearing their gifts; and Christ on his Mother’s lap stretching out his hand to receive the crown being given to him, an indication that he accepts the tribute. From the 9th century onwards the Wise Men are depicted kneeling in western art, a motif borrowed from court ceremonials and, until the Early Middle Ages, not seen as a theme of piety and worship. The appearance of the three Wise Men is a combination of traditional and new ideas. The artist retained the different ages – one old, one middle-aged and one young man – depicted since the 12th century which represented the ages of life. From then onwards, and more often as of the 14th century, particularly in German art, they also symbolised the universal church on the three known continents. Hence, occasionally since the 12th century and more frequently from the 14th century onwards, particularly in German and Dutch art, one of them was shown as a black man, thereby emphasising the adoption of Christianity on the three continents then known (“gens ad Christum conveniens”).

The adoration of the Magi was conceived of as the pagan world’s acknowledgement of a tribute to God who had revealed himself in the form of the Child born of a Virgin. The Wise Men were the first gentiles to acknowledge Christ’s divine nature by the light of the faith. According to St Augustine, the Adoration of the Wise Men was, together with the adoration of the shepherds, a prelude of Christ’s unifying function, the complete redemption of all men.

Our Lady is depicted in the painting as Sedes Sapientiae or Throne of Grace, meaning the priesthood of Our Lady, a figure of the Church. Considering this point in further depth, the author writing the continuation of the Latin Chronicle by William of Nangis (d. 1300) for the year 1375, relates how the kings of France attended the high mass of the Epiphany and how, during the offertory, they approached the altar displaying all the pomp of their royal majesty, carrying precious vessels like the Wise Men containing gold, frankincense and myrrh as a tribute to the King of kings, represented by the presbyterian, thereby asserting and consolidating Christian royalty.

Running along the lower and right sides of the frame is an inscription taken from Matthew 2: 11, “ET · AP[ER]TIS · THESAVRIS · SVIS · OBTVLER[VN]T · EI · MV[N]ERA · AVR[VM] · /TH[V]S · ET · MIRRA[M] ·”.

This was an excerpt from The Great Hours of Anne of Brittany commentary volume by Carlos Miranda García-Tejedor (Doctor in History). Our thanks to Moleiro Editor for this text and images. You can learn more about this Books of Hours by visiting: www.moleiro.com