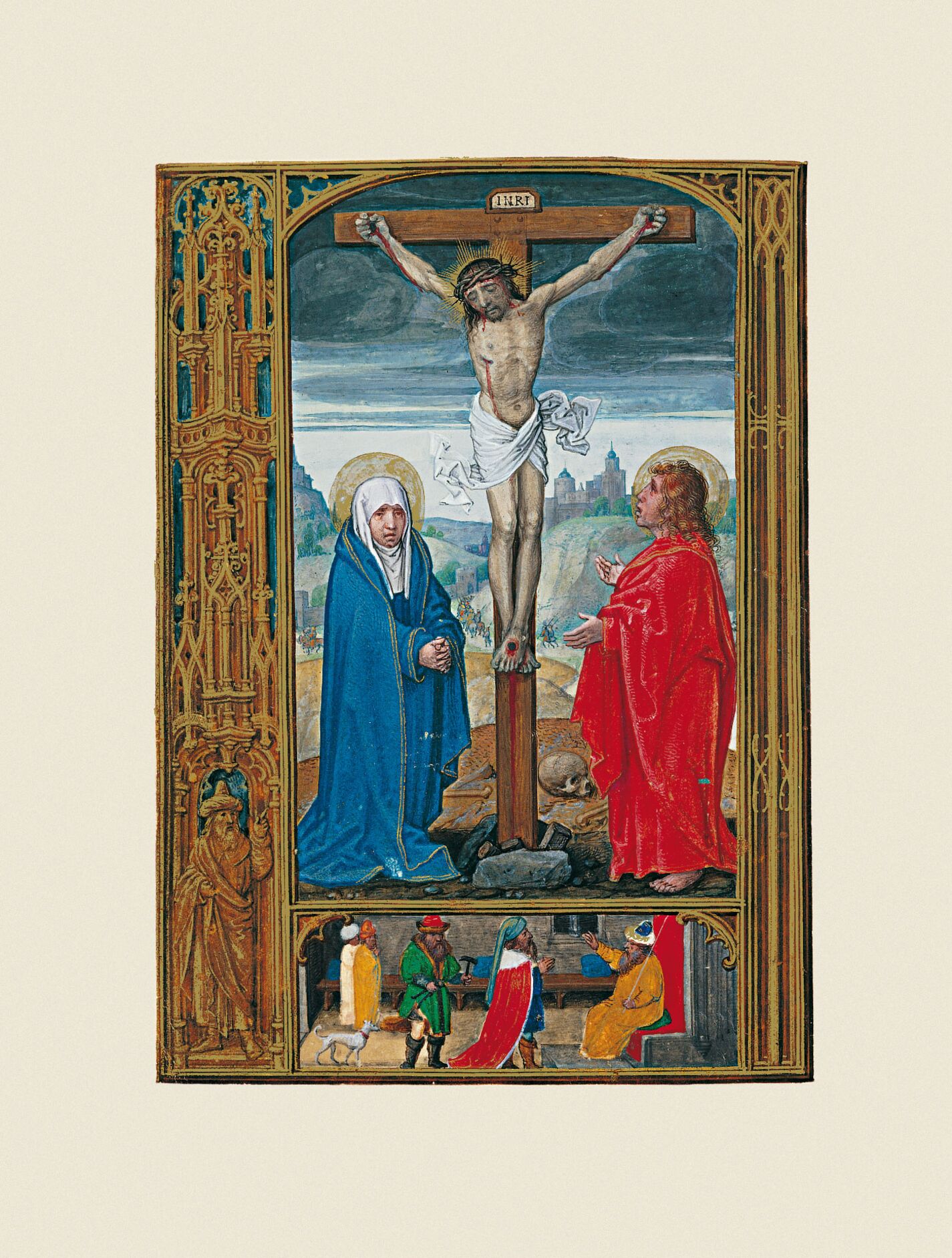

The crucifixion features just the main characters, the first being Christ, already dead, nailed to a tau cross without a suppedaneum, with a sign reading “inri” above the crossbar. Although blood is not shown gushing, it flows over the forearm, abdomen and the cross down to the ground. Standing on the right of the Lord is the Virgin with her hands clasped and a sorrowful expression. St John is shown in profile dressed in red on the left, opening his hands and looking at Jesus. Behind the cross are the skull and bones which, according to the legend, belonged to Adam. The unruly soldiers return to Jerusalem in the background. Apart from Christ’s floating loincloth and the appearance of St John in profile, which endows an otherwise rather motionless scene with movement, the composition is practically identical to the one in a series of works by Simon Bening, beginning with the Diksmuid Missal (lost during the fire in the Town Hall of the city where it was housed during World War I) and continuing with the Flowers Book of Hours (f. 29v) and the Hennessy Hours (f. 96v). No reference is made to the thieves, everything being focussed on the moment following the Lord’s death and the key figures of his mother and St John. The earliest extant representation of Christ crucified accompanied by Our Lady and St John is to be found in the relief on an ivory plaque made in northern Italy circa 420-430 (London, British Museum). Both figures appear in one of the miniatures in the Rabbula Gospels, made in 586 . This theme of eastern origin showing the Virgin on the right of her son and St John on the left, appeared in the West towards the 9th century, as revealed by a miniature in the Otfried von Weissenburg Gospel Harmony, circa 868 (Vienna, Österreichische Nationalbibliothek, Cod. 2687, f. 153v). Countless representations appear from this time onwards showing just these three figures. Naturally enough, as this iconographical theme evolved over time, Christ’s appearance and the Virgin’s more or less pronounced gestures changed. She almost always appears standing, unlike in other fifteenth- and sixteenth-century crucifixions showing her swooning in the arms of St John or the holy women.

Depicted in the scenes in the bottom border on f. 12v is Joseph of Arimathea accompanied by Nicodemus carrying a hammer and tongs, asking Pilate, seated on a stone throne and holding a long staff of authority, for permission to bury Christ. Two courtiers in eastern garb watch them. Next to Nicodemus is a dog.

Carlos Miranda García-Tejedor

Doctor in History