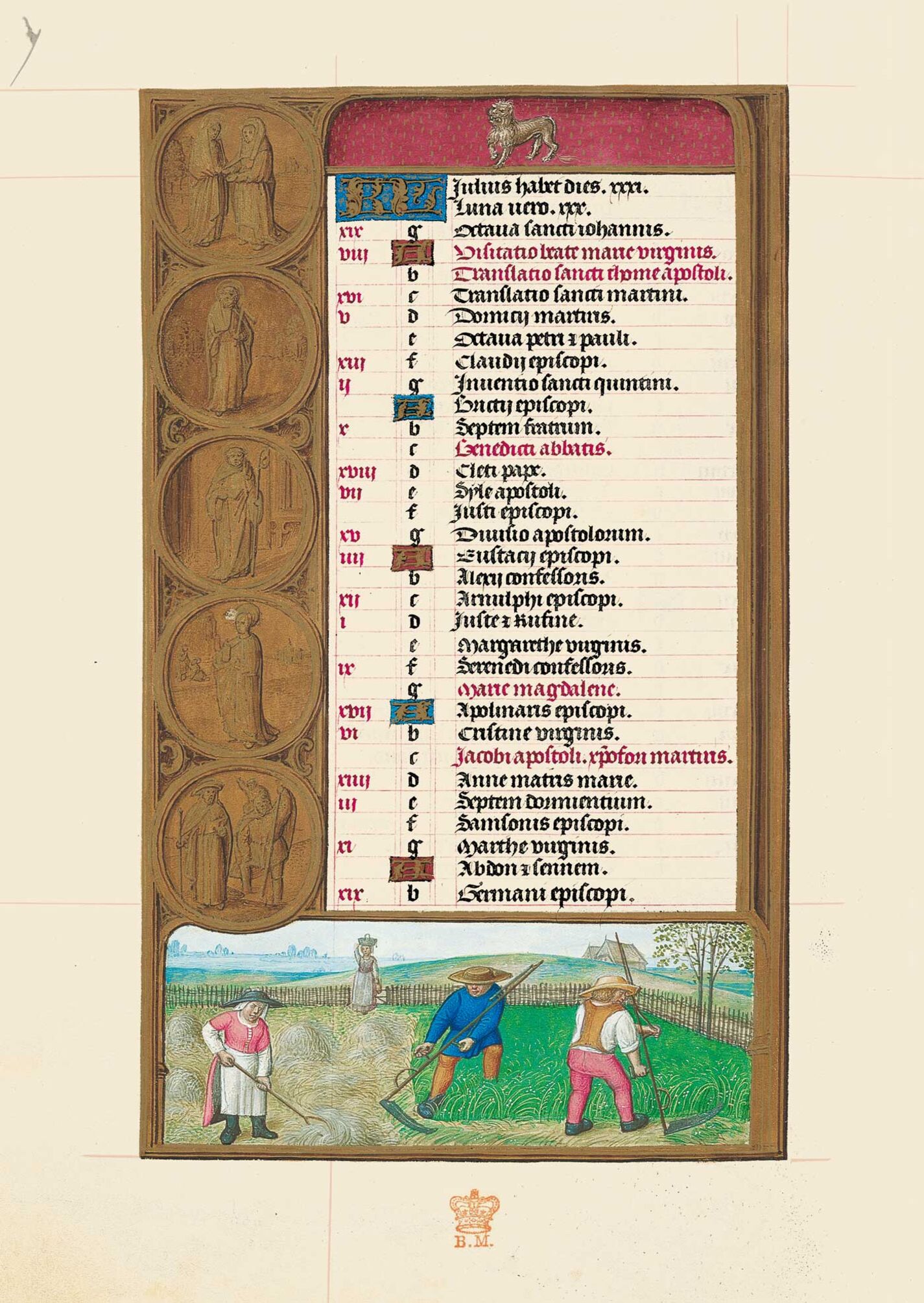

Leo is depicted as a roaring lion walking in quite a natural manner, as revealed by its bulk and fierce expression.

The medallions located on the left side concern the different main feasts of the month of July which are, from top to bottom, the Visitation, St Thomas, St Benedict, St Mary Magdalen and finally, St James and St Christopher.

The Visitation was first included as a feast in 1263 when St Bonaventure (1218-1274) introduced the feast of the Visitatio into the Franciscan calendar. From 1389 it was celebrated by the entire Roman Catholic Church and, since then, it has been one of the Marian commemorations. It was moved in the 15th century to July 2nd to mark the end of the great Western Schism. Until the end of the Middle Ages there were no separate images of the Visitation. Its history can, however, be traced back to the 5th century, in Syria, as revealed by the Monza phials and the Cappadocia frescoes, although the scene does appear as a complement to the Annunciation. The medallion in the Hours of Joanna of Castile shows the Virgin, with her cloak covering her head, allowing a pregnant St Elizabeth, with cornets to indicate her married status and older age, to grasp her hand in greeting. This gesture suggests a condescending welcome, regardless of the status of the two women and their mutual good intentions when they meet.

The second medallion contains a portrait of St Thomas standing between trees and holding an architect’s set square in reference to his stay in the East, a tale of Gnostic origin which nonetheless became popular in the Middle Ages , as revealed by the Acts attributed to the apostle, the Breviarim apostolorum, and The Golden Legend. According to this tale, Abban, one of the envoys of King Gundafor of India, invited him at the forum of Caesarea to set sail with him to build a palace for his sovereign. Christ appeared to him to encourage him to do so. When he reached the capital, the monarch placed his wealth at his disposal for the construction of the palace. The apostle built a celestial palace by distributing the money amongst the poor. Two years later when the king returned from a long journey and heard what had happened, he felt he had been betrayed and ordered him to be imprisoned. However, he forgave him when his brother, Gad, who had died shortly before, came back to life to tell him that in heaven he had seen the palace built for him with the charity of his architect. This fabulous journey to India, which St Augustine had doubts about, is completely apocryphal: it may have stemmed from an alteration of St Epiphanius’s text, due to reading India instead of Iudaea.

Shown in an indoor setting is St Benedict of Nursia, with an abbot’s crosier and the vestments of the order he founded, holding a book, possibly in allusion to the text of the Rule, according to the iconography of the classical tradition of the author standing and reading his work. In Dialogues, St Gregory the Great (540-604) tells the life of several saints venerated in his times. He dedicates the second book to St Benedict, born in Nursia, Umbria, around 480. The pontiff heard about the life of Benedict the monk and abbot from several of his immediate disciples. His twin sister, St Scolastica, had been consecrated to God as a child. Whilst a young student in Rome, Benedict decided to change his life radically and in around the year 500 he withdrew to lead a hermit’s life in a cave called Sacro Speco near Subiaco lake, where several monasteries were founded subsequently. In 528, he moved to the region of Monte Cassino, where he founded a famous, new monastery in a former acropolis that had been dedicated in Antiquity to the worship of Jupiter, where he wrote the Rule for monks and where he was to live until his death in 547.

The following medallion shows St Mary Magdalen in the foreground, upon what seems to be a high plateau, holding a jar of ointment in her right hand. The saint is depicted on the right in the background in front of some rocks on her knees trying to touch Christ in the Noli me tangere scene. A city can be glimpsed on the right. She appears in the Hours of Joanna of Castile with lavish garments and in keeping with the iconography that L. Réau baptised as “Magdalen with the phial of perfume”, i.e. with the jar whose contents she sprinkled upon Christ’s feet, or it may also be the jar she took to the sacred tomb with the other two holy women . The name Mary Magdalen stems either from the town of Magdala, near Tiberias, on the western shore of Galilee, or possibly a Thamudic expression meaning “curling woman’s hair”. The New Testament mentions her as one of the women who accompanied and followed Christ (Lk. 8: 2-3) and also says that seven devils had been cast out of her (Mk. 16: 9). She is the second person to be named at the foot of the cross (Mk. 15: 40; Mt 27: 56; Jn. 19: 25; Lk. 23: 49). She saw Christ lying in his tomb and was the first known witness of the Resurrection. The Greek Fathers all differentiate the three persons: the “sinner” in Luke 7: 36-50; the sister of Martha and Lazarus in Luke 10: 38-42 and Jn. 11; and Mary Magdalen, whereas most of the Latin fathers deem these three to be one and the same person. The Greek church maintains that the saint withdrew to Ephesus with Our Lady, where she died and that her relics were transferred to Constantinople in the year 886 where they are preserved. However, according to the French tradition, Mary, Lazarus and several other persons went to Marseilles and converted all Provence. Magdalen is said to have withdrawn to a hill called Sainte-Baume where she adopted a life of penance for thirty years. When she was about to die, angels carried her to St Maximinus’s oratory in Aix where she received the viaticum. Her body has lain since then in an oratory built by St Maximinus in Villa Lata, or San Maximin as it came to be called. History remained silent about these relics until the year 745, when, according to the chronicler Sigebert, they were moved to Vézelay out of fear of the Saracens. There is no record of their return but in the year 1279, when Charles II, King of Naples erected the Sainte-Baume monastery for the Dominicans, the tomb was intact and had an inscription explaining why they had been hidden.

Finally, the last medallion features a double portrait of St James and St Christopher, since the feast of the two saints is commemorated on the same day. St James appears on a river bank in a pilgrim’s hat and a soutane over his tunic, a pilgrim’s staff in his left hand and a book in the right, either in reference to the gospel attributed to him or in order to identify him as a saint bearing God’s word. St Christopher, with his feet in the water, is robust in appearance and grasps a long rod firmly. Upon his shoulders is Christ, in the form of a child, waving his right hand. Although St Christopher is one of the most popular saints in the East and West, virtually nothing is known about his life and death. According to legend, an unbelieving king (from Canaan or Arabia) had a son in answer to his wife’s prayers to Our Lady whom he called Offerus (Offro, Adokimus or Reprebus). He dedicated his son to the gods Machmet and Apollo. As the years went by, Offerus became remarkably tall and strong and decided to serve only the strongest and the bravest. He served successively a powerful king and Satan but felt that both lacked courage, the former because he was always terrified by the mere mention of sin and the latter because he feared the sign of the cross at the roadside. He searched for a new master for some time until he found a hermit who told him to dedicate his strength to Christ, and who taught him about the Faith and baptised him. Christopher, as he was known from then onwards, did not dedicate himself to either fasting or prayer, but voluntarily agreed, for God’s sake, to carry people from one side of a wide river to the other upon his shoulders. One day he carried a boy who grew continually heavier until it seemed that he was carrying the entire world upon his shoulders. The Boy said he was the Creator and Redeemer of the world and to prove who he was, he ordered St Christopher to drive his staff into the depths. The next day, the staff had turned into a palm tree laden with fruit. The miracle caused many conversions which angered the prefect of that region, Dagnus of Samos, in Lycia. Christopher was imprisoned and, after being cruelly tortured, was decapitated. The Greek legend may date from the 6th century and by the mid 8th century had spread throughout France. St Christopher was originally just a martyr, and is remembered as such in old martyrologies. Several authors tried to prove the existence of St Christopher the martyr, including the Jesuit, Nicholas Serarius in his treatise on litanies and Molanus (1633-1722) in his history of sacred paintings. The earliest paintings of the saint, in the monastery on Mount Sinai, date from the times of Justinian (527-65). Coins bearing his image were cast in Würzburg, Würtermberg and Bohemia. Statues of the saint were also positioned at the entrance to churches, dwellings and often on bridges. Many of these images and paintings bore the inscription, “he who contemplates the image of St Christopher will not faint or fall on that day.”

Finally, the scene in the bottom section depicts two peasants reaping hay for fodder with their scythes in an isolated farm surrounded by a fence. The tasks of tedding and scattering the hay were carried out by women with a pitchfork (as shown in the picture) or children, prior to being stored in haystacks. The summer heat is alluded to by the clothes: the peasants are wearing straw hats to protect themselves from the heat. One of them has a cloth shirt with the sleeves rolled up, a simple doublet and long breeches, whilst the other man is dressed in a short tunic and breeches, and the female peasant in a shirt, smock and basquine with an apron on top. Another woman in the background carries a basket on her head.

This theme, dating back to Antiquity, as shown by the Arch of Mars in Reims depicting the hay harvest for the first time as a representation of the month of July, was to reappear in Carolingian art, albeit in a schematic manner, before entering the art of the High Middle Ages as can be seen in the Wandalbert Martyrology. The hay harvest marks the start of the summer tasks, although its exact date varies according to the climate and the region, appearing in July in Flemish calendars. The two trees on the right hark back to certain earlier, French menologies such as those of Mimizan, Brie-Comte-Robert and Civray, in which the tree on the edge of the pasture area indicates how far the meadows have encroached upon the wood. This connection is logical bearing in mind that this image does not appear in any Italian calendars, despite the great plantation movement of the 12th century in central Italy. Fences may be related to the profits that grazing was expected to yield, which gave rise in the 13th century to an increasing interest in pasture land amongst ecclesiastics, the wealthy, the nobility, the bourgeoisie and the more fortunate peasants. These expectations drove them to cultivate isolated, fenced farms that were removed from peasant solidarity and collective conflicts, in a desire to escape from the obligations arising from communal pastures and flocks. Along with woods, meadows constituted a basic element of the peasant economy since the reaped grass in the storage areas of sheds in the country was used as fodder for livestock in winter. The need for fences to protect these prata under threat from the increasing development of sheep breeding is often mentioned in literature. From the 13th century onwards, the disappearance of woods and meadows restricted the basis of livestock. In order to increase hay production in response to the growth in livestock, artificial meadows were sown on land reclaimed from woods: ploughmen created fenced meadows, meadows to produce hay.