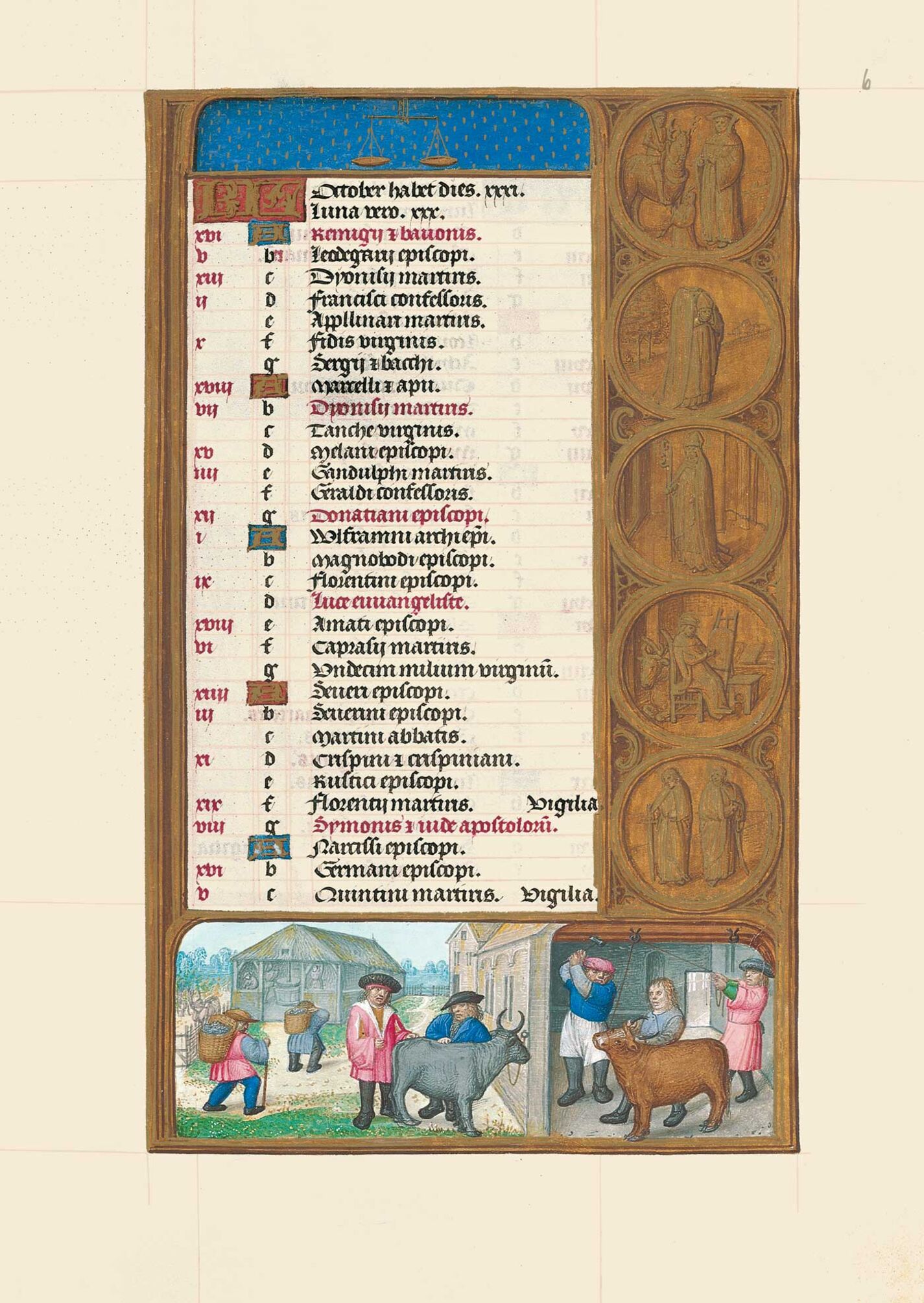

Libra is depicted as scales consisting of merely thin pans hanging from the horizontal line of the area dedicated to the constellations. According to St Isidore, this constellation “is so called because on the eighth day of the calends of October, the sun is in this sign and forms an equinox”, i.e. it coincides with the autumn equinox when, in middle latitudes, the days and nights are of the same length.

The medallions along the right side show St Remigius alongside St Bavo, St Dionysius the Areopagite, St Donation of Reims or Bruges, St Luke with his theriomorphic animal, and St Simon and St Judas.

St Remigius, whose father was Emile, Count of Loan, was born in Cerny or Laon in 437 and died in Reims on January 13th 533. His feast is celebrated on October 2nd. He studied literature at Reims and was soon elected Archbishop of Reims when just twenty-two. From then on his main aim was to propagate Christianity in the realm of the Franks. The tale of the return of the scared vessels that had been stolen from the Church of Soissons confirms the amicable relations between him and Clovis (c. 466-511), King of the Franks, whom he converted to Christianity with the help of his wife, St Clotilda (c. 474-545) and St Vedastus of Arras (554-?). Clovis gave Remigius large areas of land upon which the latter built and endowed many churches. With the pope’s consent, he erected bishoprics at Tournai, Cambrai and Terouanne, Arras and Laon. His relics were housed in the cathedral of Reims, but Hincmar (c. 806-882) had them taken to Epernay during the period of the Norman invasion, before being moved, in 1099, at the instance of Leo IX, to the Abbey of Saint-Remy. The feast celebrated in October, as pointed out by Jacobus de Voragine, is intended to commemorate the transfer of his remains, and not his death, commemorated in the month of January.

St Bavo –apparently Prince Albine, count of Hesbaye– was born in Brabant, near Liege in the year 589. He married the daughter of the Merovingian count Adilone, with whom he had a daughter called Agletrude. Being a landowner he led a comfortable life: when he needed money, he sold his servants as slaves to neighbouring landowners. When his wife died, Bavo blamed himself for this tragedy: he ceased his dissolute life and sank into a moral crisis that was the starting point of his conversion. By that time, St Amandus (584-679) was preaching in the region of Ghent. After listening to one of his sermons, Bavo approached him and, upon his advice, got rid of all his possessions including the property he owned in Ghent. He gave it to St Amandus, who built a monastery there which Bavo entered as a monk. To expiate his sins, he underwent such great mortifications that when he died, the name of the monastery was changed from St Peter’s to St Bavo’s. He became a disciple of St Amandus and followed him in his apostolic pilgrimages. He realised after a certain period that the austerities of life in the monastery were not sufficient to satisfy his desire for mortification, and returned to Ghent where, with St Amandus’s consent, he built a small cell where he lived the ascetic life of a hermit until his death some three years later, around 659. He was buried in the monastery in Ghent.

In keeping with the usual iconography, St Dionysius the Areopagite is depicted as a saint with his head detached from his body, i.e. standing, decapitated and with his head in his hands. He appears in an outdoor setting with trees and a slope that could be the side of a mountain. This saint has been confused with Dionysius of Paris, for the tale of the former has been combined with the legend. St Dionysius the Areopagite is said to have been born in Greece of distinguished parents, several years after the Saviour’s birth. In his desire for knowledge, he studied philosophy and astronomy in the school at Athens, and subsequently travelled to Egypt to further his studies in mathematics. Upon returning to his home country, he was raised to the rank of judge for his wisdom and eloquence. He became one of the first judges in Areopagus, which was, at that time, the most prestigious court. Around the year 51, on one of his missionary travels, St Paul came to Athens, preaching the doctrine of the one and true God, as a result of which, the Gentiles accused him before the courts. There, the apostle spoke about the incarnation of the Word, the resurrection of Christ and the final judgement. Amongst those who were converted and baptised was Dionysius, who was his disciple from then on (Acts 17: 15-34). This is all the information available about St Dionysius the Areopagite. The confusion between St Dionysius of Paris and St Dionysius the Areopagite arose in the 9th century because of Hilduin, abbot of Saint-Denis, who was commissioned by Louis the Pious (778-840) to write the saint’s biography, in which he declared the two to be the same person. According to this historically impossible version, the Areopagite travelled to Rome and Pope Clement I (88-97) sent him to preach to the Gauls, which he did first in Arles and then in Paris, where he and his companions were tortured and then handed over to the executioners to have their throats slit outside the city upon a hill next to the ancient site of Paris. The sentence was carried out on that hill, henceforth known as Mons Martyrum or Martyrs’ Mount (Montmartre). According to the legend, St Dionysius’s body stood up, picked its head up in its hands and, led by an angel, walked three kilometres to the abbey that bears his name today.

San Donatian of Reims is depicted in an indoor setting, in episcopal vestments with a crosier and mitre, in front of a cloth of honour. According to the legend of this saint, which was not very widespread, he was born in Rome and was the seventh bishop of the French city, a post he held from 360 to 390, the year of his death. The remains of this confessor saint were kept as relics in Corbie (near Amiens) and subsequently in Torhout. Charles the Bald (823-877) donated his relics to Count Balduin of Flanders who, in 863, laid them to rest in the church of Bruges, which currently bears the saint’s name and which was promoted to cathedral rank in 1559. He is the patron saint of Reims, Cambrai and Bruges.

St Luke is shown dressed in a cassock with a tippet and half cap, sitting on a high-backed chair working at a painting – presumably of the Virgin – upon an easel. Seen behind him is a representation of his theriomorphic animal, the winged ox.

Finally, the last medallion features the portraits of the apostles St Simon the Zealot and St Jude of Thaddeus. Both bear the attributes of their martyrdom: St Simon, a sword, and St Jude of Thaddeus, a sabre. The two saints are associated in the legend and in the iconography because they preached the Christian doctrine in Syria and Mesopotamia, and they also took an epistle and image of Christ to Abgar, King of Edessa. St Jude cured the monarch’s leprosy by stroking his face with the Lord’s epistle. After arguing with Persian magi, they tore down the idols in the temple and, according to certain legends, had their throats cut, although most legends do not say how they were killed.

Depicted in the foreground in the bottom scene is a bourgeois and his representative looking at and touching the back of an ox for sale to check its quality. Inside the shed of a longa domus, another animal is being slaughtered. One man pulls a cord going through a heavy ring nailed to a beam in the roof to raise the animal’s head, whilst another holds its head by the horns. The butcher, identified by his white apron, stands by to strike the deadly blow with his mace. In the background on the left are three peasants –one merely sketched, outside the fence– garbed in short gowns and hose, carrying panniers full of grapes to a building to be crushed in a screw press by one worker whilst another seems to pour the juice obtained into vats or casks.

In France, many scenes, particularly Romanesque scenes, feature cattle rearing. Nevertheless, their infrequent appearance, unlike that of other animals such as sheep, goats and pigs, may be due in part to the low numbers of animals cared for by peasants. A few manuscripts depict the slaughter of oxen at the end of the year. The illustration in the Hours of Joanna of Castile, like those in similar manuscripts, undoubtedly indicates the economic clout of a nobility or bourgeoisie able to purchase and sacrifice these expensive animals. This theme did, however, become very commonplace in illustrated, Flemish calendars in the Late Middle Ages and early Renaissance years.

Like cereal harvesting, vintage tasks were depicted in most northern menologies since, along with the products derived from cereal, wine was another cornerstone of a peasant’s staple diet. In October, the scene of wine decantation, in comparison with its infrequent representation in French and Italian cycles, played an increasingly important role. Since Antiquity these scenes have had an important, iconographic tradition. The late-Roman aristocracy was particularly fond of grape-gathering putti in the decoration on sarcophagi, being a motif that referred to Dionysian beliefs and recreated the ideal of country life in the Virgilian Golden Age. Vintage scenes were also usual in the country calendars in the mosaics in Roman villas, as shown by those in Cherchel and Saint-Romain-en-Gal. The contribution made by ancient art was added to by that of Carolingian illustration which was to evolve and be enhanced by the appearance, in the Gothic period, of landscape and decorative details that gradually came to be on a par with other scenes typical of the month –as can be seen in the Aquila Tower in Trento castle– or, as was the case in the Hours of Joanna of Castile and other manuscripts related to it, to occupy a secondary role.