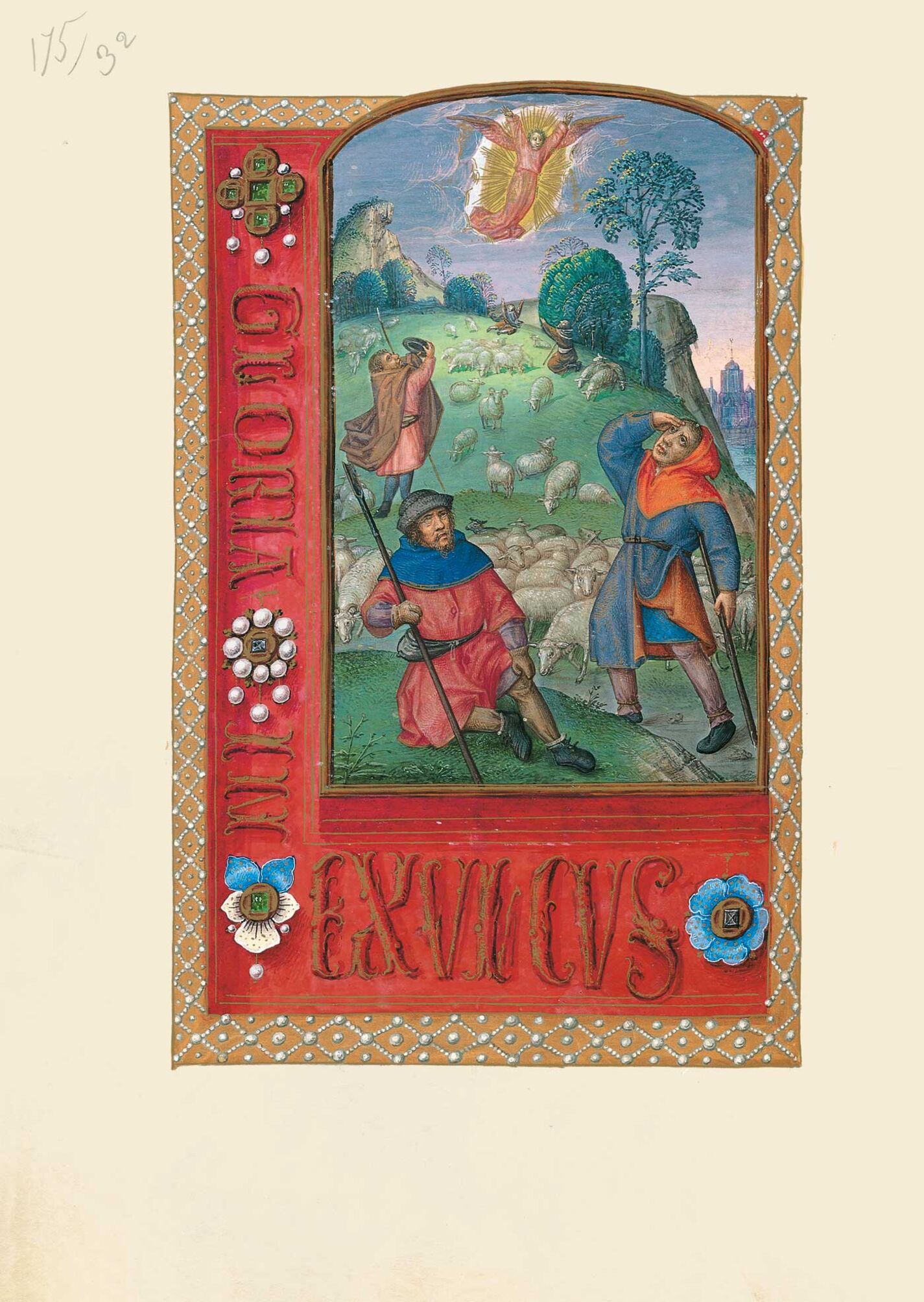

Within the cycle of the childhood of Christ, the iconographic motif usual in tierce is the annunciation to the shepherds. The image depicts five shepherds, rather coarse in appearance and with expressive gestures, at different distances and making different gestures to convey their feelings about the happening. The two in the background on their knees gesture in surprise – in a way similar to those in the background in the painting on f. 89v, with f. 95v being a sort of amplificatio of the previous one – in response to the sudden appearance of the angel with a golden nimbus, against a white background symbolising the open sky, stretching out his arms to proclaim the good news, represented graphically by the words written in golden letters emerging from his lips, “gloria in excelsis deo”. The shepherd in the background holds his cap expressively in front of his face so as to see what is happening without being blinded by the glory of the Lord who surrounded them in his light. Finally, the one on the right in the foreground, shields his eyes with his hand, whilst the one sitting on the left seems to begin to react and looks up. The angel makes the announcement on a promontory, the place where divine manifestations usually occur, to the right of which a city intended to have a rather oriental appearance can be seen.

This theme had had precedents in the East since the 5th century and appeared as a separate Nativity theme in Byzantine art. In Carolingian art it appeared both separately and alongside it, but with a meaning of its own. It was in this period that the angel began to be depicted in flight and surrounded by a light emanating from his body. The shepherds gaze at the heavenly messenger: a detail that always featured in subsequent works. The landscape illuminated by the light radiating from the angel appeared towards 1328 in the cycle by Taddeo Gaddi in the Santa Croce in Florence. At the close of the Middle Ages it was unusual to find the annunciation to the shepherds as a separate image, except in the lengthy cycles such as those appearing in certain devotional books. In this period, when the shepherds were depicted not in an idealised manner but as coarse country folk, the angel was almost always shown hovering, with a cloud as an attribute, as if descending from heaven. He speaks to the shepherds from overhead and they listen in amazement, in silence or with great excitement that spreads to their livestock. They sometimes express their joy by playing horns, recalling the classical pastoral theme. The composition of the two shepherds in the foreground (one standing and the other sitting) is similar to the compositions in a Flemish book of hours (Oxford, Queen’s College Library, Ms. 349, f. 94r) and a book of hours attributed to the Master of Edward IV of Scotland and Gerard David, made in 1486 (Escorial, Library of the San Lorenzo el Real monastery, Ms. Vitr. 12, f. 78v). Finally, the facial traits of the shepherd on the right are similar to those of one of the fourteen faces attributed to the Master of the Houghton miniatures, made in Ghent towards 1475-1485 (Berlin, Staatliche Museen, Kupferstichkabinett, KdZ 12512).

The annunciation to the shepherds is the first epiphany: its image is that of the Jewish people who received the news of the birth of Christ first. According to the Fathers of the Church, they can also be seen as a type of the future priests safeguarding the faithful from the perils of the world, in which case the brightness the shepherds saw is the grace poured upon the priests who fulfil their mission well.