Atlas Miller: Cartographic secrets and the Magellan expedition

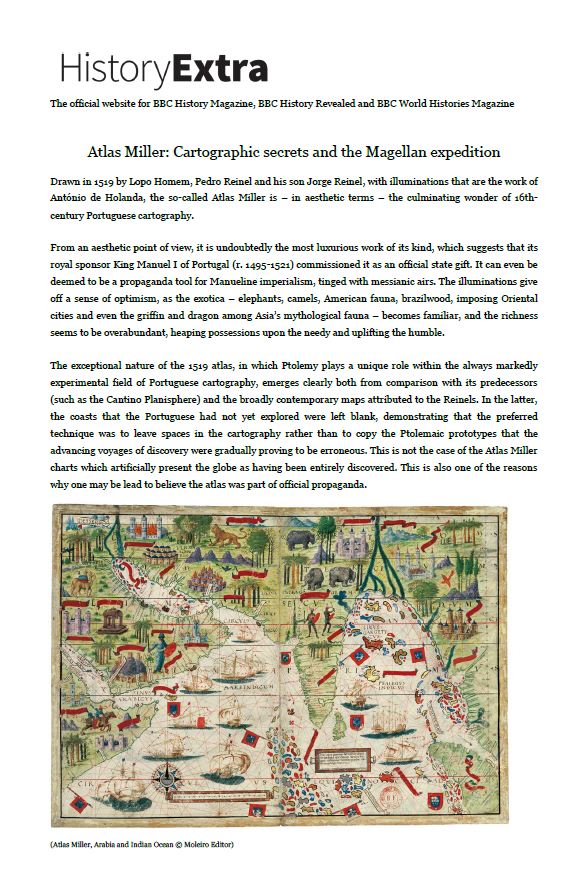

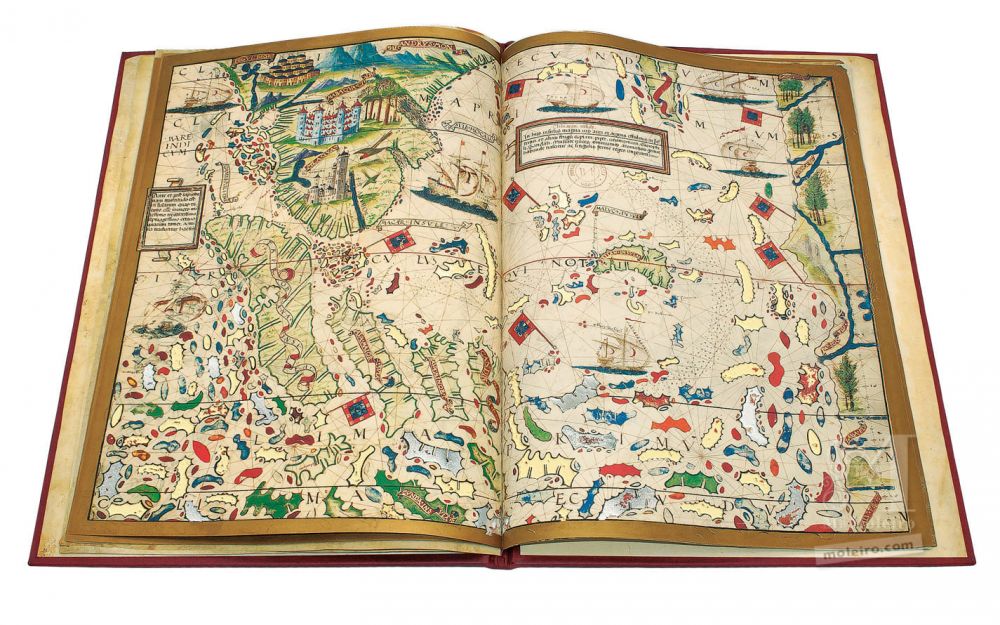

Drawn in 1519 by Lopo Homem, Pedro Reinel and his son Jorge Reinel, with illuminations that are the work of António de Holanda, the so-called Atlas Miller is – in aesthetic terms – the culminating wonder of 16th-century Portuguese cartography.

From an aesthetic point of view, it is undoubtedly the most luxurious work of its kind, which suggests that its royal sponsor King Manuel I of Portugal (r. 1495-1521) commissioned it as an official state gift. It can even be deemed to be a propaganda tool for Manueline imperialism, tinged with messianic airs. The illuminations give off a sense of optimism, as the exotica – elephants, camels, American fauna, brazilwood, imposing Oriental cities and even the griffin and dragon among Asia’s mythological fauna – becomes familiar, and the richness seems to be overabundant, heaping possessions upon the needy and uplifting the humble.

(Atlas Miller, Arabia and Indian Ocean © Moleiro Editor)

The exceptional nature of the 1519 atlas, in which Ptolemy plays a unique role within the always markedly experimental field of Portuguese cartography, emerges clearly both from comparison with its predecessors (such as the Cantino Planisphere) and the broadly contemporary maps attributed to the Reinels. In the latter, the coasts that the Portuguese had not yet explored were left blank, demonstrating that the preferred technique was to leave spaces in the cartography rather than to copy the Ptolemaic prototypes that the advancing voyages of discovery were gradually proving to be erroneous. This is not the case of the Atlas Miller charts which artificially present the globe as having been entirely discovered. This is also one of the reasons why one may be lead to believe the atlas was part of official propaganda.

This is clearly shown in the chart depicting India and its surrounding lands, one of the most beautiful in the Atlas Miler. In terms of cartographic accuracy, it is divided into two parts: apart from a few minor details, the area west of Ceylon is generally a faithful depiction, only using ancient geography to counter contemporary lack of knowledge about the inland areas. From Coromandel to the east, there is far greater reliance on Ptolemaic geography in order to represent the lands which the Portuguese had not explored in any detail. India occupies the centre of the chart and it is intended as its main focus. Nevertheless, other than the rivers Indus and Ganges, both incorrectly portrayed, the image is restricted to the coastlines. Even then, the only the western coast bears any place-names, while the rest is a shapeless space covered with illuminations. It could be said that King Manuel was more interested in boasting about India than in actually showing it. By subtly combining the information brought by the Portuguese discoveries with elements taken from Ptolemy, the cartographers drew a world that was apparently fully known: a sign that the end of time was nigh, the moment when no century-old secret would remain hidden.

Yet close attention reveals it to be only a half-truth. The Atlas Miller’s maps generally stop west of the longitude of Yucatan (c. 90° W of Greenwich) and slightly east of the Moluccas (approximately 135° E), while all the Southeast Asian island area is shown in an inaccurate and imaginary form. Thus, only 62.5% of the globe is depicted, slightly over half the Earth. It would be difficult for the atlas to show anything else, since the maps were drawn in the very same year as Cortez landed in Mexico and Magellan began his voyage to the Moluccas via the west. Therefore, the lands that would be discovered two or three years later could obviously not be included.

RULER OF THE HALF OF THE WORLD

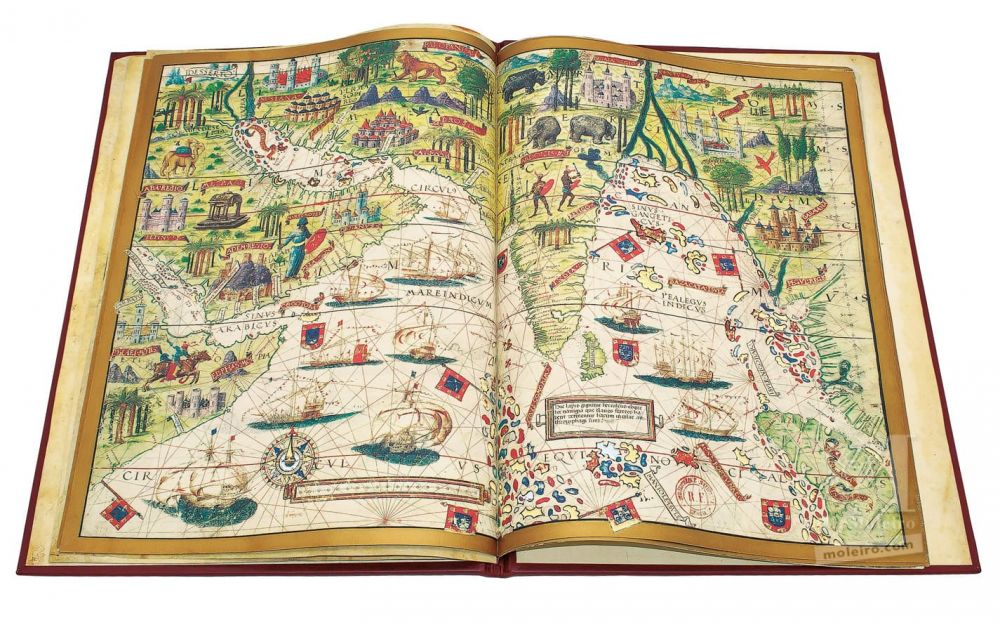

Although the Atlas Miller is now unbound and with detached pages, there is no doubt that what is referred to as the mappamundi was the first map and acted as a sort of prologue. It is worth noting that, contrary to its name, it is not a map of the entire world, but only shows the hemisphere that broadly corresponds to the side granted to Portugal by the Treaty of Tordesillas (treaty signed in 1494 which divided the world between Portugal and Castile setting up a longitudinal demarcation line 370 leagues west of the Cape Verde). Consequently, the mappamundi covers around 215° of the Earth’s circumference, namely all of the Portuguese hemisphere, as well as a 35º slice to the west in the Castilian hemisphere. However, it can legitimately be wondered whether the cartographer – who may have used Ptolemaic or mythical geography to “fill the gaps”, as indeed he did in other cases – did not deliberately omit the Castilian hemisphere so as to suggest that while Portugal had already explored virtually all of its half of the world, Castile was still taking its first steps.

(Atlas Miller, Planisphere (mappamundi) © Moleiro Editor)

Moreover, if the aim was to create a mappamundi in the strict sense of the term, the map could never be circular. It would have to be a rectangular planisphere, adopt a broadly elliptical form or comprise two circles where each represented one hemisphere.

It is interesting to note that the vision of the world found in this map matches the political positions adopted by the Portuguese crown in this period. Christopher Columbus supposed the world to be far smaller than it really is, which explains his mistaken belief that he had reached the coastline of Cipango (Japan, located around 140° E or 220° W) and Cathay (China), when he had in fact reached the Antilles and later the Venezuelan coastline, at c. 70° longitude west. It is now known that unless Asia was hugely extended to the east, Columbus’ calculation would mean reducing the circumference of the Earth by 150°, or roughly 40% of its actual size. Such was the discrepancy between this data and the perimeter of the globe that Columbus himself even advanced the hypothesis that the Earth was not spherical, but pear-shaped, broader in the southern hemisphere than in the north. For many years, Castilian cosmographers – perhaps more out of political convenience than geographical ignorance – continued to insist that the globe was indeed very small. Martín Fernández de Enciso’s Suma de Geographia, published in Seville in 1519 (the same year as this atlas was created), stated that the Tordesillas antimeridian passed through the mouth of the Ganges, which in fact lies at just 90° E. Although later geographers were more moderate, they continued to insist that the antimeridian cut through the islands of Borneo and Java, thereby leaving the Moluccas, famous “Spice Islands” sought by the European colonial powers, on the Castilian side. By painting the terrestrial globe on a larger scale – showing 215º as just half of the sphere – the cartographer who produced this atlas superbly managed to guarantee Portugal’s right of possession over those islands.

As is well known, this proved to be a thorny problem, since there was no accurate means of determining longitude at that time. In fact, it would only be definitively settled in the 18th century with the invention of the chronometer.

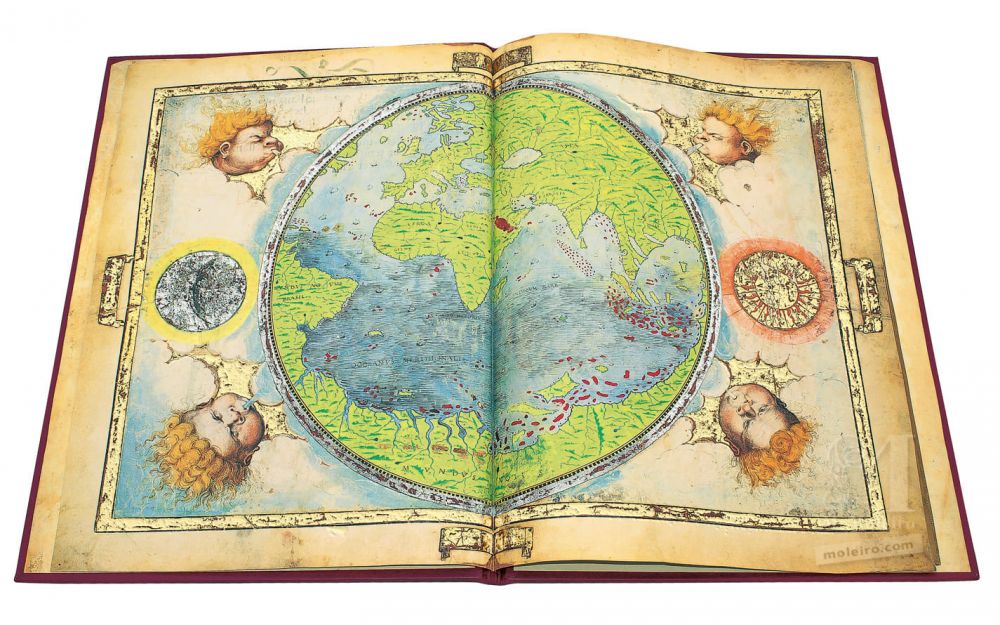

Whereas the mapamundi is a simple sketch, the remaining charts in the Atlas Miller are not only magnificently illuminated, but also created using the finest technology then available. As such, they are not portolan-chart or navigational maps, since the objective was not to serve practical ends but to convey an idea of the world. Their elaborated iconography was to support Portuguese dominion over the most important sea routes and at the same time justify imperialistic ambitions of its ruler.

King Manuel I used the title of “Lord of the Conquest, Navigation and Trade with Ethiopia, Arabia, Persia and India”. He had adopted this in 1499 when Vasco da Gama returned from his first voyage, and immediately used it in the letter through which he informed the Roman curia of his captain’s achievement. In practical terms, he fundamentally claimed the right to control all navigation in the Indian Ocean according to his economic and political whims. In common parlance, it was as if King Manuel called himself the “king of the sea”, as Martin Waldseemüller depicted in his Carta Marina Navigatoria (1516), showing King Manuel with an imperial crown on his head and a sceptre in his hand, riding a dolphin southeast of the Cape of Good Hope.

While the Castilians in the New World quickly moved on to conquest and direct administration, the Portuguese in the Orient clung on to the mediaeval system of tributes, using an implicitly imperial system of jurisdiction. The Atlas Miller demonstrates King Manuel’s proposed imperium, especially in the eastern hemisphere, through the depiction of numerous shields and banners that bear the arms of Portugal. These are scattered across islands and coastlines, not only where there was an effective Portuguese presence (as in the west coast of India and the east coast of Africa), but also in the Gulf of Bengal, the endless archipelago drawn in the southern Indian Ocean, China, the islands and shores of Magnus Sinus and even in the imaginary coast opposite the Chinese littoral. Close attention reveals another highly significant detail: the atlas makes absolutely no reference to Hinduism or other Oriental religions, either in the captions or the illuminations. Instead, it is the crescent of Islam that appears on shields dotted around the coastline of the Indian Ocean and Magnus Sinus, in every corner where the five-castled shield of Portugal does not appear, and even on the sails of the ships that criss-cross the eastern seas. The semi-naked warriors in the Hindustan Peninsula, who evidently represent the Nairs (the Hindu warrior caste in Malabar), are holding shields decorated with the half-moon, while even in China there is a man wearing Moorish dress, with a turban and cowl that recalls those of the k?z?l bash, a Shiite brotherhood from Iran. This means that the entire Portuguese expansion in the Orient can be identified with the still significant archetype of the crusade, which was invariably associated to the universal empire in utopias from the Middle Ages.

(Atlas Miller, Magnus Sinus © Moleiro Editor)

SEA VERSUS LAND

The atlas offers an unusual response to another issue that aroused a series of contrasting theories throughout the centuries of discovering the globe: whether or not there was more sea than land and if the former surrounded the latter or vice versa. The traditional response was that the sea was in principle much larger and therefore surrounded and embraced the land. Certainly, this was the position taken by Homer, who stated that the land was surrounded by the ocean (Okéanos), which he saw as a great river of flowing water. The same position was maintained by most Greek geographers and by T-O maps from the Middle Ages, where the inhabited earth was depicted in an approximately circular shape (O) divided into three continents (Asia, Europe and Africa) separated by the Tanais or Don, the Nile and, running perpendicular to them, the Mediterranean, thereby creating the T shape. Most 15th-century mapmakers – the best informed of whom was unquestionably the Venetian Fra Mauro, who completed his mappamundi in 1459 – and the planisphere attributed to Cantino adopted the same approach. Indeed, the idea that the sea surrounded the land was so convincing that some geographers went as far as to suggest that the Caspian Sea, the apparent exception to the rule, was linked to the Black Sea by some kind of subterranean canal.

The Atlas Miller takes the opposite and much rarer position that may ultimately be traced back to Ptolemy. His Geographia only describes the well-known parts of the world, from the Canaries meridian to 180° E and from 63° N to 16° S. The work’s most curious individual feature is that it shows the inhabited earth as a single continent that envelops all the seas. Thus, the Indian Ocean is sealed in to the south by an imagined land mass that connected southern Africa to China. This not only countered the traditional idea, which dated back to the time of Homer, but also the statements made by some Arab geographers, including Ibn Hauqal (fl. 943-988), Albiruni (973-c. 1050) and Abulfeda (1273-1331), who maintained that there was a sea passage between the Atlantic and the Indian Oceans.

After Bartolomeu Dias’ voyage in 1487-88, the Indian Ocean could no longer be seen as a closed sea. However, the discovery of America five years later enabled the Ptolemaic concept of an ocean ringed by terra firma to be redefined in new terms. As clearly seen in its mappamundi, the atlas shows the existence of an imaginary land-link between Brazil, Antarctica and the supposed land to the east of Magnus Sinus, which seems to be an adaptation of the Ptolemaic vision of the Indian Ocean as a close sea. In an attempt to combine experience with the underlying Ptolemaic idea, the land-link between the easternmost point of Asia to the southern tip of Africa was shifted further south, thereby connecting the Far East to the recently discovered South America.

In other words, the Atlas Miller is a rare example among its contemporary cartographical works, with Ptolemy making a triumphant return. It depicts a globe where land dominates water. Besides the three continents known in Antiquity, there was also a fourth, while the sea is surrounded by land and is nothing more than “a very large lake set in the concavity of the Earth”.

THE POLITICAL GOAL

The Atlas Miller’s option to adopt this minority opinion cannot possibly have been politically innocent. In fact, on 25 September 1513, six years before this atlas was created, Vasco Núñez de Balboa completed his crossing of the Panama isthmus and first set his eyes on the great western ocean that he called the Pacific. The results of his exploration could not have gone unnoticed in Lisbon. The discovery of the Pacific would, however, immediately result in a search for a sea passage linking it to the Atlantic. Accepting Homer’s old theory, it was based on this assumption that such a link existed that Magellan sketched out his expedition in 1519, the exact same year as the Atlas Miller was produced. Ignoring Balboa’s discovery, the cartographer of the Atlas Miller thus hinted that Magellan’s plan was not feasible and that the only route to reach the Moluccas was the one already used by Portuguese vessels: rounding the Cape of Good Hope and then crossing the Indian Ocean. If this hypothesis is true, then the decision to use a rare and apparently already outdated vision of the world must have been taken for political and propaganda purposes.

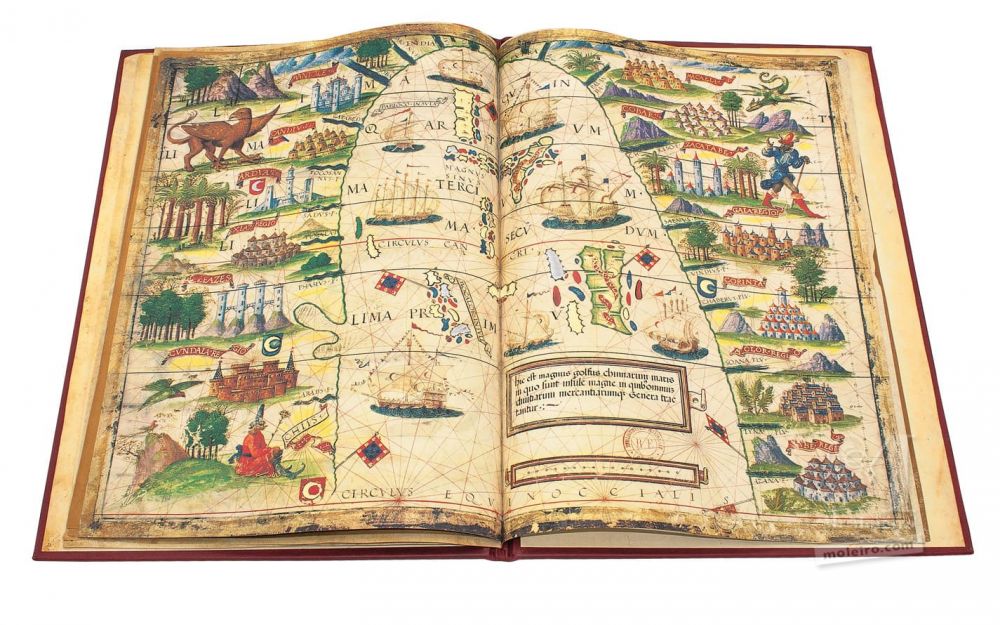

The ultimate expression of this may be found in the map depicting South-East Asia. Just like the previous charts, this one is also very beautiful, but clearly aims more to impress than to inform.

(Atlas Miller, South-East Asia © Moleiro Editor)

The entire western half of the Southeast Asian islands is chaotically portrayed as a vast labyrinth of islands, which may be a means of dissuading anybody for the prized Moluccas, as they would be lost behind an impenetrable maze of islets. The right half of the chart depicts the Moluccas Islands themselves, surrounded by imaginary islands in the Magnus Sinus, which is bordered by the supposed land mass lying to the east. The only vessels sailing this sea are Moorish, with the billowing sails on the customary one or two masts all bearing the crescent. To compensate for this, the three islands and three imaginary points on land mass have flags bearing the Portuguese coat-of-arms.

A large framed Latin caption explains:

“Islands of the Chinese. On these isles, they mine gold and silver with great energy, and besides the copious amounts of wheat and other fruits, pepper, cinnamon, clove, sandal, nutmeg and all sorts of aromatics grow, and in general, a king rules over each one”.

The Moluccas islands stricto sensu are shown on the centre of this chart by eight large, five medium-sized and nine small islands, set out in a cluster pattern. It is curious to note that the relatively accurate drawing of the Moluccas in the atlas does not seem to fit in with the intent to confuse potential competitors for possession of these islands, an aim that apparently emerges in other details. However, the goal may have been to suggest that the archipelago was well known and under control, while disguising the routes to reach it. This could explain the depiction of a gigantic set of shallows east of the Moluccas, that forms a veritable chastity belt around the much sought-after islands.

Regardless of the institution that it was intended for, there can be no doubt that the 1519 Atlas Miller mirrored the Manueline imperial ideology and pretended to repel any attempt to weaken his dominion over the most profitable maritime routes. The cartography was the ideal tool to transmit the vision of the world that suited these goals. This is why the charts of the atlas show the precious “Spice Islands” as jealously guarded by the Portuguese throughout the Indian Ocean and impossible to reach from the other side of the globe because of the imaginary border land mass enclosing the oceans. This directly contradicted the goal of the expedition being prepared by Ferdinand Magellan and financed by the rival Castilian crown, expedition that started the very same year the atlas was painted. The vision of the world unveiled on each chart countered the idea that the globe can be circumnavigated and the Atlas Miller was to officially disseminate this concept.

Prof. Luís Filipe F. R. Thomaz

Historian, Orientalist

Former Director of the Institute for Oriental Studies of the Portuguese Catholic University

You can purchase a limited facsimile edition of the Atlas Miller from the publisher M. Moleiro Editor.