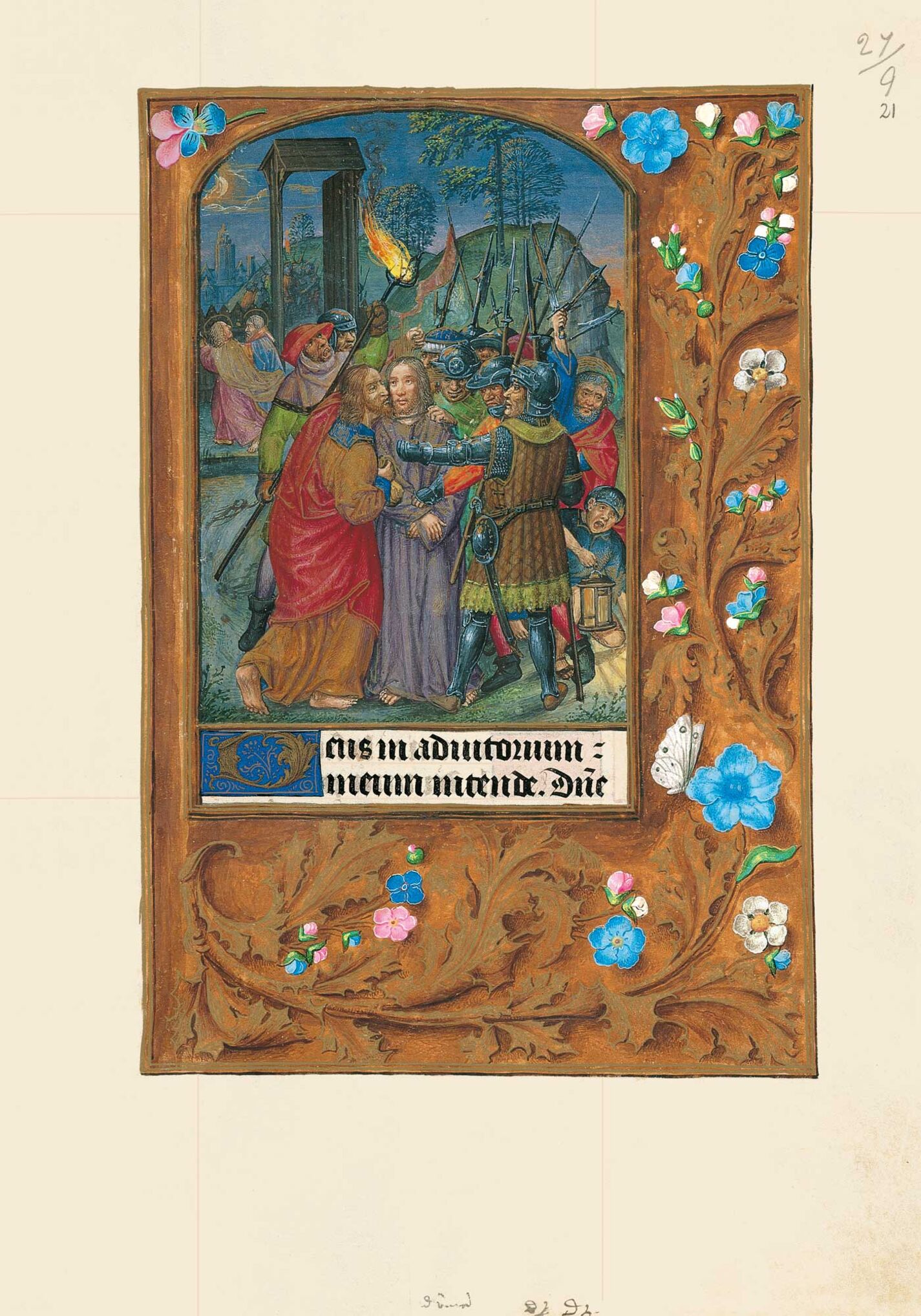

The painting shows a red-headed Judas with a prominent nose, in profile holding a bag of coins and, for the sake of decorum, moving in such as way that his head is slightly below that of the Master, kissing the cheek of a serene Christ with his hands crossed upon his stomach. Surrounding them are the soldiers, one of whom places a rope around the Lord’s neck. Several of them take him by the right sleeve and the left shoulder. One of the soldiers, garbed in brocade with leather trims covering his armour, takes him by the chest. The appearance of this soldier, posed as if taking possession of someone, shows him to be superior to all the others. Another soldier raises his fist to strike the Lord on the head. One of the guardsmen raises the torch to illuminate a scene which, in this instance, is set inside the Garden of Olives –where two disciples of different ages, including a long-haired, beardless disciple who may be identified with St John, can be seen fleeing– at a slightly later moment, as shown by the darker sky. A greater variety of weapons is present than in the previous scene: halberds, spears, scimitars and bucklers. St Peter, on the right, raises a sword reflecting the shine of the torch to cut Malchus’s ear off whilst the servant, on his knees holding a large lamp, shouts out. On the left in the background next to the garden palisade are several soldiers waiting for Christ to emerge. Jerusalem can once again be glimpsed in the form of a contemporary, Flemish city.

The betrayal was one of the first scenes of the Passion to be depicted. Its origin dates back to the 4th century, never again to disappear from medieval cycles. Even Byzantine art, which used few scenes of the Passion, featured the kiss of Judas as the only scene prior to the Crucifixion. One of the earliest extant examples is the Brescia Casket dated 360-370 (Brescia, Christian Museum). The kiss of Judas appeared later in sarcophagus sculptures, as revealed by a fourth-century relief housed in Verona. The iconographic layout is very simple: Christ, on the left, and Judas, on the right, are both shown in profile walking towards each other. The traitor is shown with his head near Christ’s head and resting his arm on his shoulder. Slight variations were subsequently added to this archetype as, for example, a miniature in the Evangeliarium of St Augustine, dated around 600 (Cambridge, Corpus Christi College, ms. 286, f. 125r), which features the guards with lit torches. One picture in the Syriac Gospels of Rabbula, dated 586 (Florence, Biblioteca Laurenziana, Cod. Plut. I, 56, f. 12r), uses the most ancient layout featuring the betrayal and arrest of Christ with few figures. The same occurs in the Stuttgart Psalter dated 820-830 (Stuttgart, Württembergische Landesbibliothek, Cod. 23, f. 8r), showing an evolved form of the embrace, which was to become an important element in the future development of this iconographical theme: Jesus, as in the Hours of Joanna of Castile, is no longer shown in profile but facing forwards with his head turned slightly towards Judas, moving from the front rather than from one side. This motif suggests an ancient pictorial tradition: the mosaic at Sant’Apollinare Nuovo in Ravenna from the early 6th century is the earliest extant example of this, the second oldest tradition. The guards waiting at the entrance to the Garden of Olives, on the other hand, possibly in reference to St John’s Gospel, do appear in the Gospels of St Augustine mentioned above. Scenes originally intended to be separate appear in combination in the monumental art of the early Middle Ages: the serene Christ facing forwards stems from the Ravenna type. When the members of the guard are separated, the scene involving Malchus –initially only alluded to by the sword in St Peter’s hand, as in the case of the Gospels of St Augustine– may be depicted as an individual scene, but over the course of time it came to be a standard part of the combined image. In that type of image, as it appears in a fresco dated around 800 in Mustiar and another in Cimitile dated around 900, the Lord, whilst being kissed by Judas, turns towards St Peter and holds his hand out to stop the apostle’s attack. In the course of time, the Lord came to be shown not only gesturing to stop St Peter’s act but also curing Malchus. This was quite usual in the Gothic period although some artists, such as the master of Naumburg cathedral and Gerard Horenbout in the Hours of Joanna of Castile, did not use it, possibly from a desire to highlight only the betrayal and arrest. Judas, however, is depicted with the physiognomy that ecclesiastical anti-Semitism applied to the Jews, i.e. with a prominent nose , red hair and dressed in yellow, the symbolic colour of jealousy used for Jews and traitors . Finally, the lantern –a torch in this case– held over Christ’s head by a soldier has been an attribute of the guard since the 12th century, indicating that Jesus was arrested at night. It is unusual for narrative cycles of the late Middle Ages not to feature the iconographic themes of the kiss of Judas and Christ’s arrest.