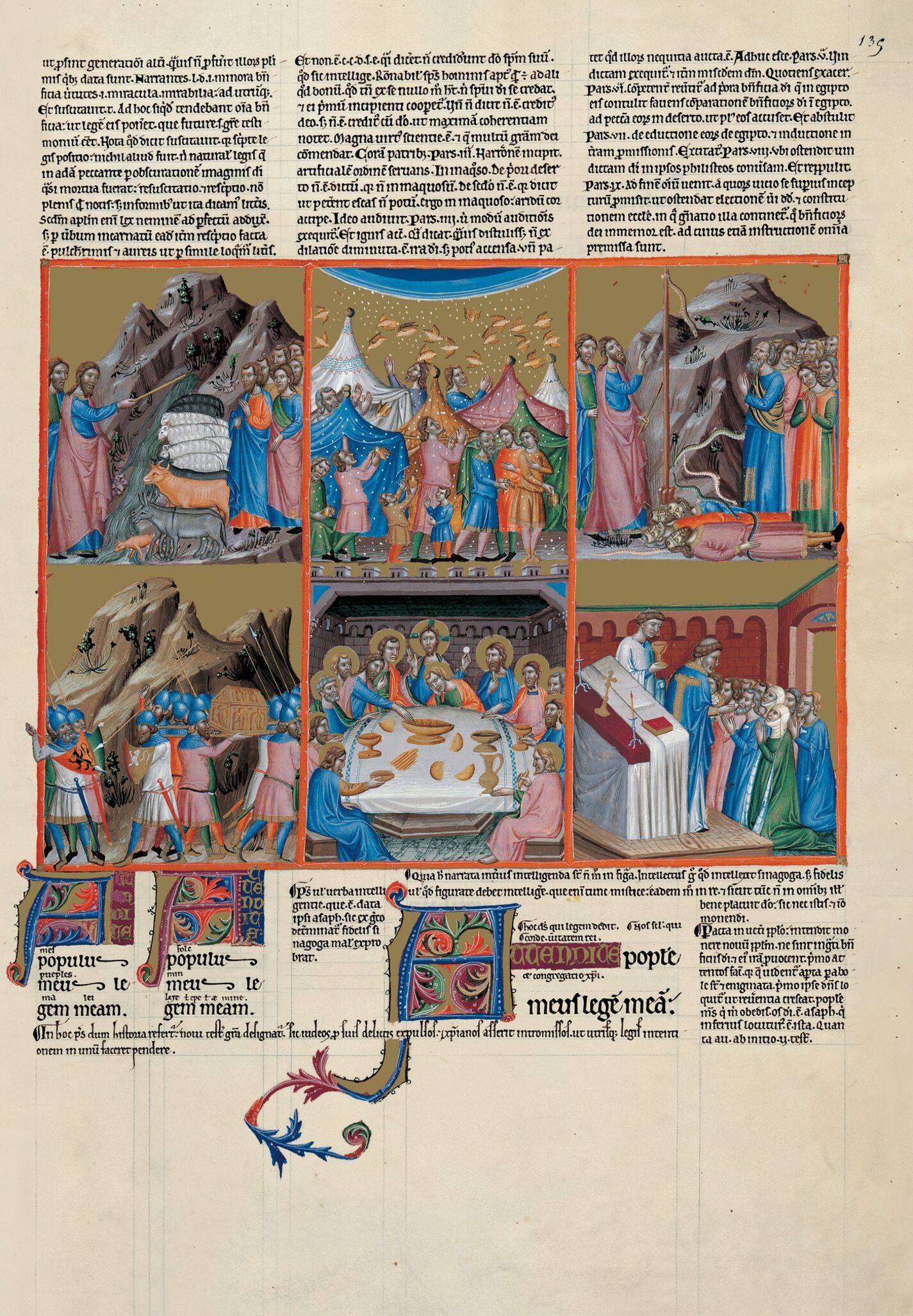

Psalm 77 exhorts people to abide by the law on account of the marvels that God is capable of working, to the benefit or detriment of his faithful, with many references to the specific tale of the Israelites in the desert after they leave Egypt. The six scenes divided into two registers reflecting this idea combine some new chapters of the Old Testament upon which the episodes of the Last Supper and a representation of communion during mass are based. The first four pictures, from left to right and top to bottom, are to a considerable extent prefigurations of the following Eucharistic images. First we see the miracle at the rock in Horeb (Ex. 17: 1-7, Ps. 77: 27) from which abundant water springs, saving the thirsty Hebrews and their animals from death thanks to the intervention of Moses who, situated in front of Aaron, touches the rock with his rod (v. 15-20). The painter shows the water flowing from above and reveals his fondness for portraying animals which are quite prominent in this episode and in others mentioned above or to be analysed later. This is followed by the manna and partridges that fall from heaven upon the camp of the tribe of Israel (v. 24-30). The white, blue, green, pink and ochre tents open and their dwellers emerge and try to catch the birds, quickly transformed into food, and also gather the manna that falls from heaven (Ex 16: 1-36). Consequently, the gift of water is now joined by the gift of the celestial delicacies that God sends his starving people and which the psalm duly describes as having fallen upon the Israelites’ camp (v. 28, Et ceciderunt in medio castrorum eorum, circa tabernacula eorum./ And they fell in the midst of their camp, round about their pavilions). It is noteworthy that no women are to be seen amongst the children, men and old men on the slow journey to the promised land after crossing the Red Sea. Reference is made to the two sacred species, the blood and the flesh, in the Exodus episodes preceding the Last Supper. However, before considering this New Testament scene, mention must be made of another two Old Testament episodes. The long psalm 77 provides the inspiration for their contents (v. 31-69). Still in the first register, we see the murmuring of the tribe of Israel that rose up again on the Moab plain against their guide and the God that brought them out of Egypt. A great many Israelites, shown lying on the ground, die from a plague of poisonous snakes. Their stiff bodies are still covered by harmful snakes. Only further divine intervention can halt the reptiles’ devastating advance, after the confession of those who had slandered Moses and his Lord. A bronze snake was built and tied to a rod. Thanks to its healing properties, people wounded by snakebites were healed at the mere sight of it (Num 21: 4-9). Deserving of mention is the pictorial quality of the repentant group representing the pardoned sinners. The face of the first of them is very similar to some of the magnificent heads that Ferrer Bassa incorporated into the Bellpuig Coronation.

Depicted in the lower register is the Ark of the Alliance being carried. This ark housed the tables of the Law and was rescued after Israel’s defeat from where it was held by the Philistines (I Sam 4-6) and defended on several occasions from enemy attacks. The miniature portrays the ark being carried and the sacred object being defended by several soldiers whose standard is a shield with a white, rampant lion, confronting others led by a warrior bearing a red shield embellished with a black griffon. The ark and its structure are particular interesting. The Jewish ark covered in gold is in the form of a Christian urn, whose box and lid are both decorated with full-length figures, possibly angels, shown in relief beneath lobulated arches. This type of pictorial solutions, which imitate metal-worked items or articles or tombs with sculpted, Gothic reliefs, also appear in the Hours of Maria of Navarre (f. 196v).

The exhortations of psalm 77 evoke the need for generation after generation to abide by the law housed in the ark and the ire of God against those who rise up against it. The sons of Ephrem of the tribe of the Philistines broke the agreed alliance (v. 10, Non custodierunt testamentum Dei: et in lege ejus noluerunt ambulare. // They kept not the covenant of God: and in his law they would not walk), forgetting the miracles of the past. Amongst such miracles, the Psalter overlooks neither the crossing of the Red Sea (f. 132) nor the miracles in the desert which provided the Israelites with delicious delicacies from God, despite those who asked blasphemously: Numquid poterit Deus parare mensam in deserto? // Can God furnish a table in the wilderness? (v. 19). In response to this way of referring to those who mistrust God (v. 19-21), the images pay tribute to his power in both the Old and the New Testaments. The miniature comes to a neat finish in the temple where the Christian consecration of the bread and wine, the body and blood of Christ, is taking place. Ferrer Bassa produces a magnificent portrait of the scene in which, in front of a altar adorned with everything necessary (valance, altar cloths, a book, a cross and two candlesticks), a tonsured priest with the paten of the sacred species in his hand and assisted by an acolyte holding the chalice, gives communion to a numerous group of kneeling people, amongst whom the two in the foreground stand out: an old man and a woman. The royal nature of the couple may be questioned perhaps, but not the nobility of the group in general.

In keeping with the psalm, the illustrations wavered between prizes and punishments, but placing particular emphasis on the former, also evoking renewed hope in eternal salvation. In this way, humanity can be nourished by the “bread of angels” (v. 25, Panem angelorum manducavit homo: cibaria misit in abundantia // Man ate the bread of angels: he sent them provisions in abundance) and save itself from the poisonous snakes lying in wait (v. 31).