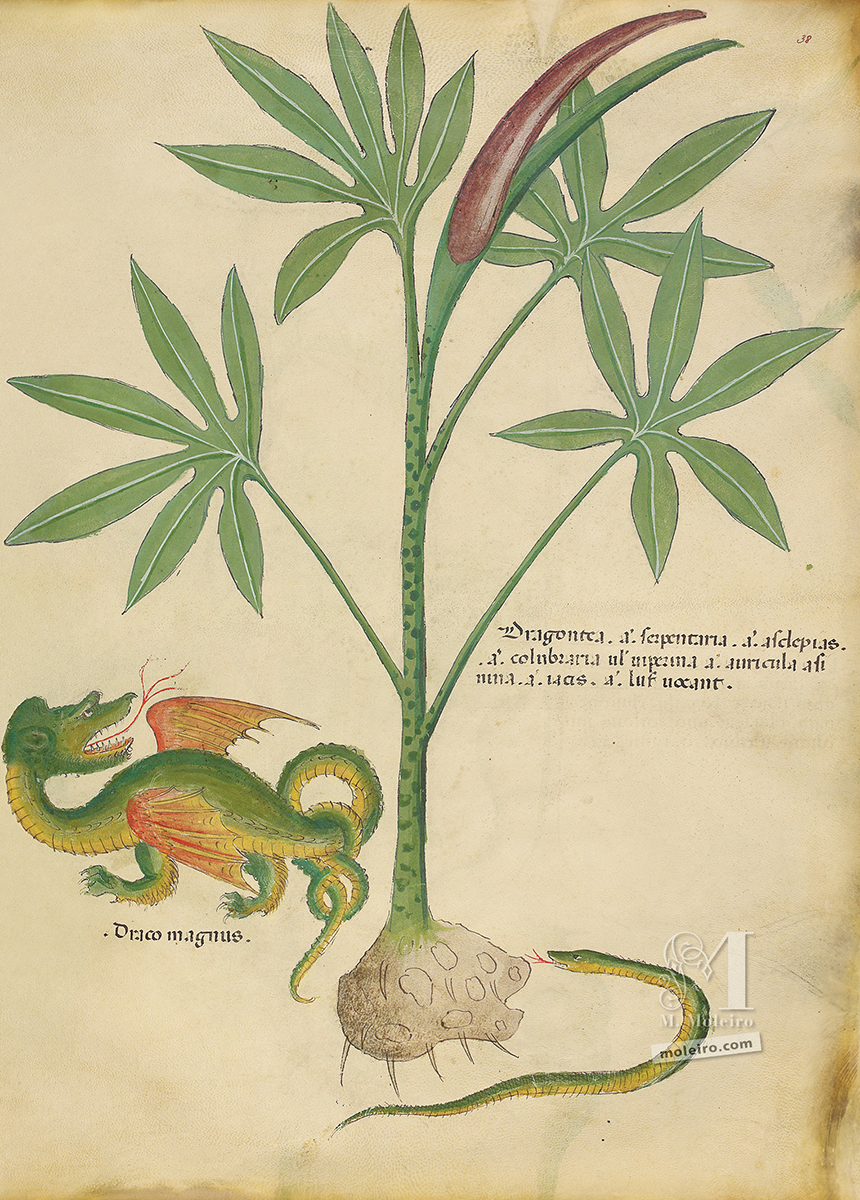

Plants are often drawn by artists, including in centuries past. Here are how two manuscripts, one from the 15th century and the other 16th century, show different ways to recreate the same plant.

The healing power of plants has been known and documented since the emergence of ancient civilizations. In Europe, one of the most reputed ancient experts on medicinal substances was the Greek physician and pharmacologist, Pedanius Dioscorides of Anazarbus. His instructions on how to recognize and use medicinal plants have been compiled, summarized, paraphrased, and glossed throughout much of the history of medicine. Although occasionally revised or corrected, Dioscorides remained the highest authority on medical botany for medieval and Renaissance doctors and the principal source for many manuscripts and printed books on the subject.

Since in order to prepare an herbal remedy one had to be sure both which plant species o use to treat the condition and what this species might look like, books facilitating the identification of plants have for centuries played a crucial role in medical practice. Much care had been taken to accurately depict the species described by Dioscorides, and in many cases the result was not without artistic merit.

Two examples of those lavishly illustrated herbals are the manuscripts made in Italy about a hundred years apart from each other and now in the British Library: the Tractatus de Herbis (Sloane MS 4016) created in 1440 and Mattioli's Dioscorides illustrated by Cibo (Additional MS 22332) created circa 1565 by the artist and botanist Gherardo Cibo.

Here is how this plant is described in Cibo's manuscript (f. 53v):

"The dragon arum grows in shady places close to hedges. It has an upright stem two cubits high and as thick as a walking-stick, variegated in colour and smooth, so that it looks like a snake; it is mottled with blotches, mostly purplish; its leaves are folded one within the other, similar to those of the dock. The seed grows at the top of the stem in a cluster, first ash-coloured, and then, as it ripens, it grows saffron-coloured and red. Its root is large, round, white, covered with a thin skin. The plant is harvested when the seed is ripe; the juice is then squeezed from it and it is put to dry in the shade. The root is dug up when harvesting the fodder crops; it is cut into pieces which are skewered and dried in the shade. The root, drunk in watered wine, is warming. Boiled or roasted with honey, it makes a good linctus for asthma, ruptures, convulsions, phlegm coming from the head, and coughs; drunk with wine it has an aphrodisiac effect.[...] Moreover, it is said that those who rub their hands with the leaves of this plant, or who carry its root in their hands, cannot be bitten by vipers."

Dioscorides explains that root of the cinquefoil is good for many ailments, almost like a cure-all. Ha also advises that the black seeds of peony, when "drunk with honeyed water or with wine, are good against the anguish that oppresses sleep at night and also against suffocation and pains of the uterus."

Dioscorides mentions that this plant is a remedy for inflammations and induces sleep.

The plant properties come from the commentary volume of the facsimile edition of Mattioli's Dioscorides illustrated by Cibo. The quotes were adapted from sixteenth-century Italian by Elena Artale (Consiglio Nazionale delle Ricerche).

The facsimile editions of the Tractatus de Herbis, Mattioli's Dioscorides illustrated by Cibo and other illuminated manuscripts are available at www.moleiro.com.