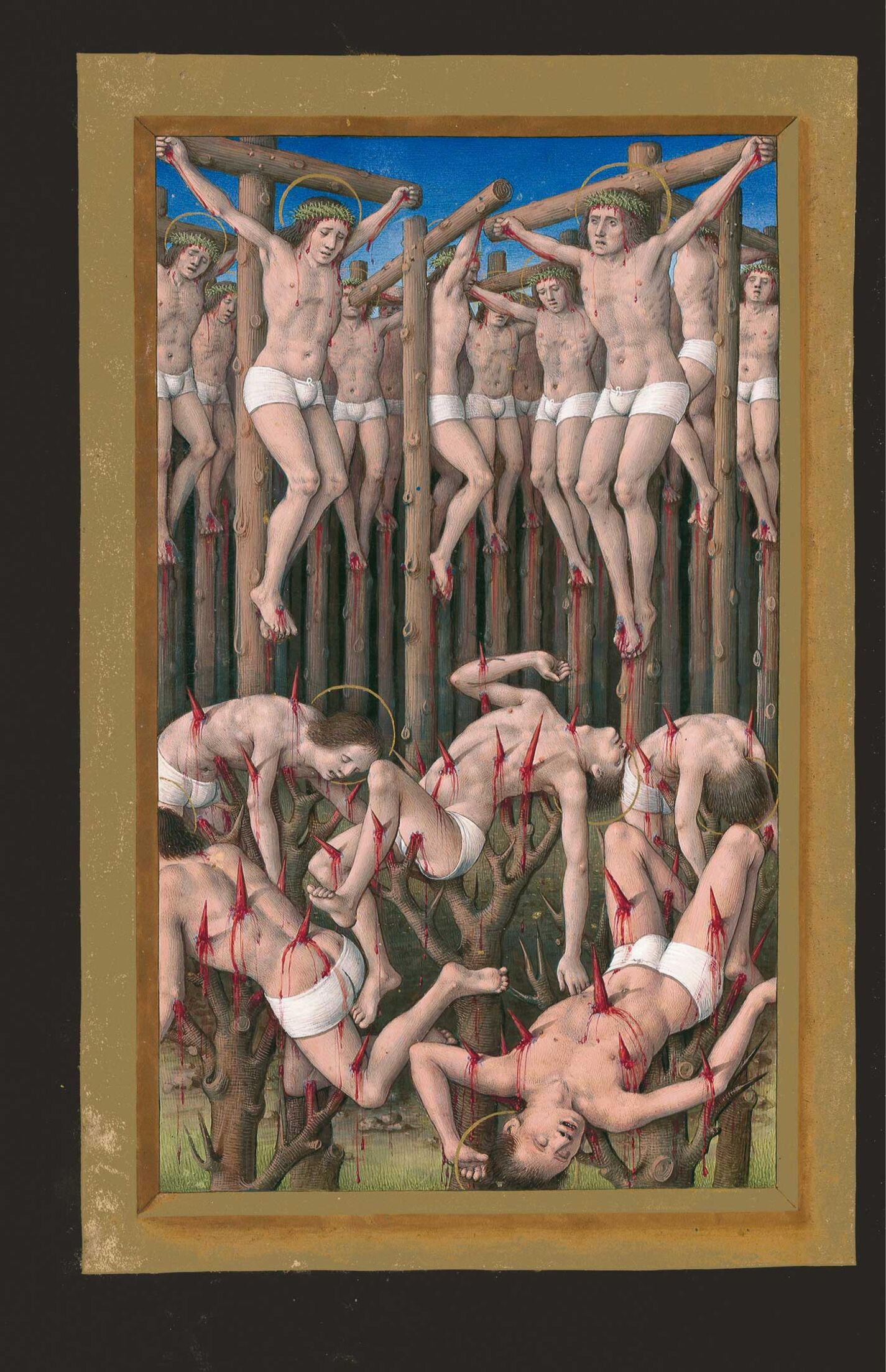

The painting is divided into two parts. Depicted in the lower section are five men cast upon dry acacias with long thorns piercing them through and through, whilst the upper part shows a cluster of crosses upon which there are sixteen men with haloes, all of whom are almost naked. The foreshortening of the man in the bottom, right-hand corner and the man further back lying face upwards next to him produce a remarkable impression of depth, as does the diagonal layout of the three crosses in the centre. Because of the subject matter, this is one of Jean Bourdichon’s most dramatic paintings although suffering is portrayed in a restrained manner by merely flowing blood and the impaled martyrs in the foreground.

Mention is made in the Martirologio Romano of a group of ten thousand martyrs on June 22nd: “On mount Ararat, the martyrdom of ten thousand martyrs who were crucified”. The narrative of this collective martyrdom was established in the 12th century along the lines of the martyrs of the Theben Legion, to inspire crusaders with courage and trust. The name Acacius, the Roman centurion who led them, is an indication of the torture the martyrs suffered: in the Middle Ages, the proper name of the Roman centurion referred to the thorn bush now known as acacia. Acacius suggested the idea of a spike or thorn: akis in Greek. As a result, people imagined that St Acacius and his companions were flogged with thorns and condemned to walk bare-footed over iron spikes and impaled on sharp acacia branches. The popularity of these martyrs peaked in the 15th and early 16th centuries. They were invoked, above all, to bring relief to the dying.

Legend has it that in the times of emperors Adrian and Antoninus, in the year 120, the people of the Euphrates region revolted against the Romans with an army of more than one hundred thousand men. They were confronted by an imperial contingent of sixteen thousand men and many of the Romans, frightened by the number of the enemy, fled. Nine thousand legionaries, however, spurred on by tribune Acacius chose to risk death for the glory of Rome rather to save their lives by cowardice. Before setting off to fight, they made ordinary sacrifices to ensure the protection of the gods, but far from strengthening their resolve, this worship weakened it and made them unable to withstand the clash with their opponents. An angel appeared to them and said, “If you beg the Lord in heaven for help and believe in Jesus Christ, victory will be yours”. They believed the apparition and decided to convert to Christianity. They managed to defeat their enemies, which strengthened their faith even more. The angel led them to mount Ararat where the two emperors, together with seven pagan kings, asked them to come back to receive their reward and give thanks to the gods. But they answered that they had become Christians and that thanks to Christ they had overcome their enemies. The leader rebuked them for rejecting the religion of the Empire and threatened that if they did not change their opinion, they would be condemned to death as lèse-majesté criminals but Acacius bravely declared that “far from being criminals of divine and human lèse-majesté, they rendered to the true God the honour he was due and to the emperor, the service they owed him, begging for his conversion and the prosperity of his state”. The soldiers then prepared to stone these converts to the name of Jesus but the stones rebounded against the assailants and their hands withered. Fearing the torture not, another one thousand men from the pagan armies joined ranks with the martyrs, bringing their number to ten thousand. Beforehand, they were ordered to strip them of their clothes, tie them up and flog them. They were also forced to walk along a road of spikes but the angels removed them. The idea was to inflict upon them all the tortures suffered by the Son of God: they were crowned with thorns, their sides were pierced with spears, they were flogged and abandoned to the insults of the soldiers. Finally, many of them were crucified on mount Ararat, whilst others were thrown from the top of a cliff into an abyss full of stakes. Towards the sixth hour, the martyrs asked God for everyone venerating his memory to have a healthy mind and body, and a voice in heaven said that their wish would be granted. They died at the same time as Jesus on the Cross. The angels buried the bodies that fell from the cluster of crosses during an earthquake.

The painting is divided into two parts. Depicted in the lower section are five men cast upon dry acacias with long thorns piercing them through and through, whilst the upper part shows a cluster of crosses upon which there are sixteen men with haloes, all of whom are almost naked. The foreshortening of the man in the bottom, right-hand corner and the man further back lying face upwards next to him produce a remarkable impression of depth, as does the diagonal layout of the three crosses in the centre. Because of the subject matter, this is one of Jean Bourdichon’s most dramatic paintings although suffering is portrayed in a restrained manner by merely flowing blood and the impaled martyrs in the foreground.

Mention is made in the Martirologio Romano of a group of ten thousand martyrs on June 22nd: “On mount Ararat, the martyrdom of ten thousand martyrs who were crucified”. The narrative of this collective martyrdom was established in the 12th century along the lines of the martyrs of the Theben Legion, to inspire crusaders with courage and trust. The name Acacius, the Roman centurion who led them, is an indication of the torture the martyrs suffered: in the Middle Ages, the proper name of the Roman centurion referred to the thorn bush now known as acacia. Acacius suggested the idea of a spike or thorn: akis in Greek. As a result, people imagined that St Acacius and his companions were flogged with thorns and condemned to walk bare-footed over iron spikes and impaled on sharp acacia branches. The popularity of these martyrs peaked in the 15th and early 16th centuries. They were invoked, above all, to bring relief to the dying.

Legend has it that in the times of emperors Adrian and Antoninus, in the year 120, the people of the Euphrates region revolted against the Romans with an army of more than one hundred thousand men. They were confronted by an imperial contingent of sixteen thousand men and many of the Romans, frightened by the number of the enemy, fled. Nine thousand legionaries, however, spurred on by tribune Acacius chose to risk death for the glory of Rome rather to save their lives by cowardice. Before setting off to fight, they made ordinary sacrifices to ensure the protection of the gods, but far from strengthening their resolve, this worship weakened it and made them unable to withstand the clash with their opponents. An angel appeared to them and said, “If you beg the Lord in heaven for help and believe in Jesus Christ, victory will be yours”. They believed the apparition and decided to convert to Christianity. They managed to defeat their enemies, which strengthened their faith even more. The angel led them to mount Ararat where the two emperors, together with seven pagan kings, asked them to come back to receive their reward and give thanks to the gods. But they answered that they had become Christians and that thanks to Christ they had overcome their enemies. The leader rebuked them for rejecting the religion of the Empire and threatened that if they did not change their opinion, they would be condemned to death as lèse-majesté criminals but Acacius bravely declared that “far from being criminals of divine and human lèse-majesté, they rendered to the true God the honour he was due and to the emperor, the service they owed him, begging for his conversion and the prosperity of his state”. The soldiers then prepared to stone these converts to the name of Jesus but the stones rebounded against the assailants and their hands withered. Fearing the torture not, another one thousand men from the pagan armies joined ranks with the martyrs, bringing their number to ten thousand. Beforehand, they were ordered to strip them of their clothes, tie them up and flog them. They were also forced to walk along a road of spikes but the angels removed them. The idea was to inflict upon them all the tortures suffered by the Son of God: they were crowned with thorns, their sides were pierced with spears, they were flogged and abandoned to the insults of the soldiers. Finally, many of them were crucified on mount Ararat, whilst others were thrown from the top of a cliff into an abyss full of stakes. Towards the sixth hour, the martyrs asked God for everyone venerating his memory to have a healthy mind and body, and a voice in heaven said that their wish would be granted. They died at the same time as Jesus on the Cross. The angels buried the bodies that fell from the cluster of crosses during an earthquake.